You define yourself as a ‘multi-disciplinary visual artist, community organiser, designer, and producer’. I wanted to start by asking about the interplay between these different parts of your life and practice?

I like to say that my work meets at the intersection of art and nightlife culture. I’ve been drawing since I was six years old; it has been one of my key points of communication for as long as I can remember. I began organising within nightlife about five years ago, when I designed the first flyer and logo for MASISI, a queer Afro-Caribbean platform that explores the Caribbean diaspora through events and programming in Miami. Through my time in the collective, I began to use my art to participate in local grassroots organising and co-producing different activities throughout the city.

I read that you’re self-taught. What was your route to becoming an artist? Did you have a creative childhood? And was there a moment that made you realise you might want to be an artist?

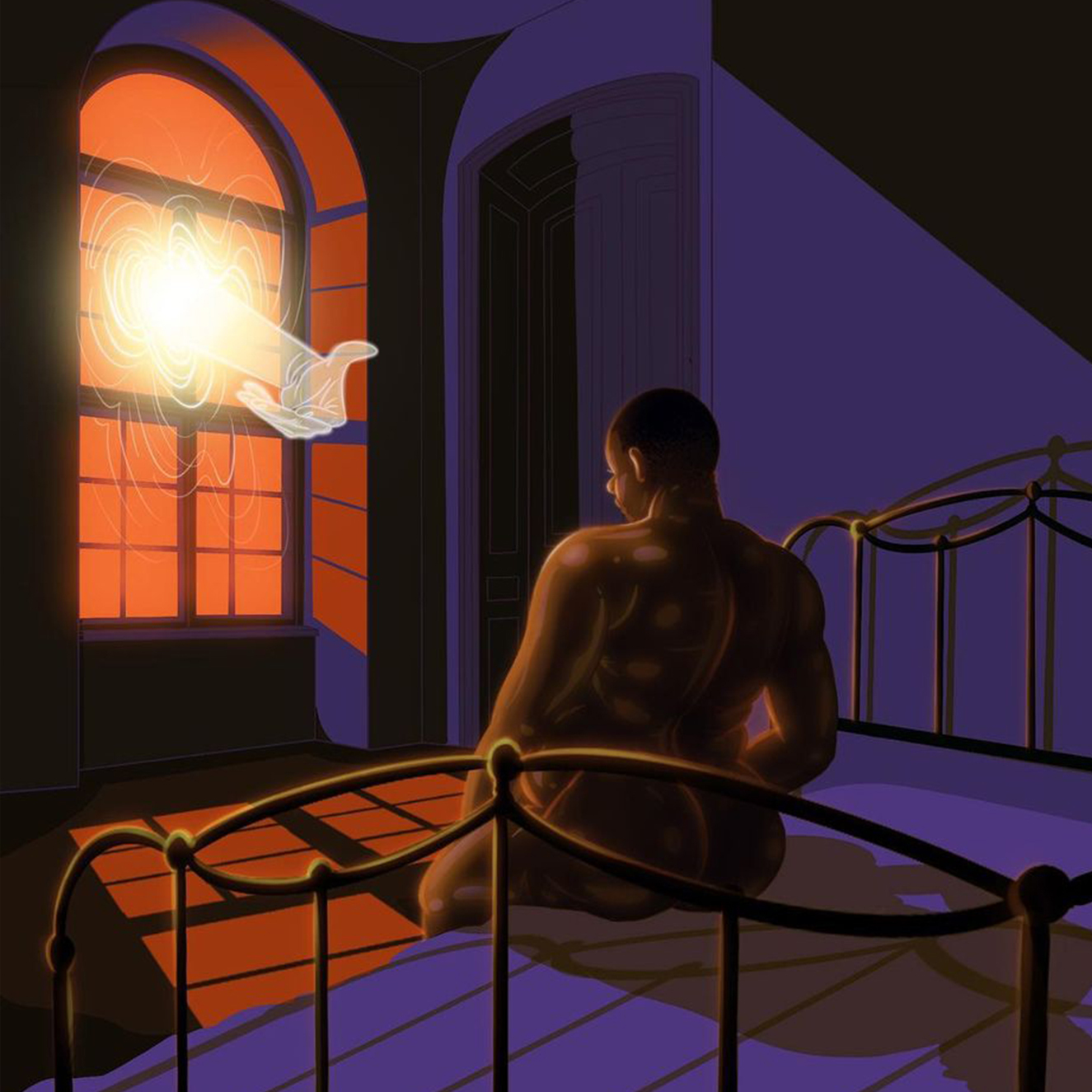

As corny as it is to say, I feel like art found me. I was a very flamboyant, queer and animated child. I didn’t have many friends, and I began drawing imaginary characters at a very young age for solace and companionship. I was always inspired by things that were out of my reach. I grew up in a small rural town in central Florida, but was always fascinated by the luminescence and luxury of the ‘golden era’ of hip-hop and R&B, so I would be inspired by music videos, magazine spreads and CD covers. Growing up with TV shows like Proud Family, Little Bill and Static Shock, I always knew I wanted to create cartoons. But I was interested in making specifically black-queer cartoons, to fill the void of representation in the cartoon world.

I feel like art found me

Part of your very multifaceted output is comics, which are arguably the visual mode most connected to storytelling. I wanted to ask how important narrative is to you?

Comics to me are just analog animations, storyboards as people call them. Through storyboarding, I get to combine my love for drawing and documenting by building a narrative. This narrative-building connects me back to the child version of myself who wasn’t always happy with their real surroundings, so decided to create their own ideal surroundings. Some call it escapism, but I don’t know, I like to think this all ends up becoming a roadmap to manifestation.

In another interview you said, “Throughout the history of cartoons we’ve seen Black characters be depicted either negatively or as the minority of the cast. I’m working diligently to change that.” Do you think of your work as political?

Well, that depends – how do you define political? I’ve come to learn that people from different classes, races, backgrounds, and privileges all have different meanings of the word political. For me, as a bigger-bodied Black-trans person, I don’t really see how anything I create can not be political. My identity (whether I want it to be or not) is at the intersection of THE most marginalised communities across the global human race.

You have a very distinctive aesthetic – how did you know you’d arrived at your ‘signature style’?

All of my cartoon characters are Black. Therefore our skin glows in ways that read as both iridescent and cartoonish. Growing up I struggled to understand the beauty of having dark skin. I was often told I was ‘too sweaty’ or ‘too oily,’ and as a result I avoided sun or any form of perspiration to prevent looking ‘too shiny’. But, illuminating my characters in this way helped me accept the beauty and power in melanated skin. It’s a sentiment that carries through in all of my work: Taking something painful, and transmuting it into something iridescent.

I’m really interested in how community comes into your work. You’ve described the characters in your images as ‘fan art’ of your friends, and you’ve worked with artists like Kelsey Lu. For you, how important is it to be part of an artistic community?

I didn’t realise how influential being a part of an artistic community was until I came across (F)EMPOWER back in 2019 in Miami. (F)EMPOWER is a queer-feminist political collective fighting fascism through cultural confrontation in South Florida. My time in the collective radicalised me politically, and taught me not only the power of community, but the power of the arts within activism. Discovering collectives like MASISI, (F)EMPOWER, and the global queer-nightlife community has provided endless inspiration for my art. Through radical theorising, deep political study, spiritual-diasporic education, and astral-projectal raving, I’ve been able to artistically transport both myself and my audience to an alternate world devoid of convention.

Sometimes it’s hard to recognise your own growth

How do you know when something you’re working on is finished?

I don’t necessarily know if anything I’ve created is ‘finished’. A lot of times, I just have to pull myself away to consider something done. If time is non-linear, and art is subjective, then anyone could pick up where I left off on a piece, in their own interpretation.

Experimentation, and constant growth as an artist, seems very integral to how you work. Is there any new part of your practice that you want to start exploring?

Thank you for stating that. Sometimes it’s hard to recognise your own growth, but more recently I’ve been taking time to sit with the work once it’s complete, in order to really process the artistic journey in full. My next chapter is embarking on animation. Ironically, animation has been the goal for as long as I can remember with my art. Unfortunately, growing up I was unable to acquire the proper education around this meticulous skillset. Then my illustrations grew to be so popular that I felt compelled to explore that part of my practice to the best of my capability. Now that I feel like I’ve overcome the digital artist stereotypes, and am embarking on showing in galleries and being part of the institutional art world, I feel like it’s definitely time to shift focus into the next stage of my practice. Wish me luck!

Read More: Momo Gordon’s Balancing Act