Can you talk a little bit about how you started the label?

José Moura: It started as a split project between two sides. Me and Marcio [Matos] DJed regularly, and we started a night with two other guys who made music. We began entertaining the idea of maybe starting a label for their stuff, and other local stuff we were starting to enjoy, stuff that could stand internationally too.

On the other side, you have Pedro [Gomes], who is no longer with the label, and Nelson [Gomes], who have a cultural association called Filho Único. They put on shows, manage some artists, and are musicians themselves, so we knew their work and respected them, and so we decided to approach them with this project, for a label. We knew they had a lot of local contacts, and they had access to music that we didn’t have, through being managers and regularly organising live shows. When we did approach them, it happened that they were also thinking about a label, so we kind of melted the two ideas together, and that’s how Príncipe was born.

It wasn’t initially the plan for the label to be dedicated to this style of music. But we quickly realised that the amount of music we were receiving or listening to within this genre, or ‘family’ of music, was so mind-blowing, and so unknown, and so different from everything else locally and internationally, that we really felt we had to do something for this music.

We wanted to help the sound come out of the neighbourhoods

We wanted to help it come out of the neighbourhoods, where it was already big in some ways, there was already a circuit going on, and for example DJ Marfox was already playing abroad in Europe for some communities abroad. But it was unknown to us, and to a dance music audience, it was only going on in the neighbourhoods outside of Lisbon, in the periphery.

In an interview with Pitchfork you said, “Without DJ Marfox there would be no Príncipe.” How integral he has been, and how have you built trust between your artists and your label?

JM: DJ Marfox was absolutely essential, of course. He was the first one to give us access, firstly to his own music, and then to the music of some younger kids who looked up to him. Nelson and Pedro, through Filho Único, had started working regularly with DJ Marfox, putting on shows with him, for maybe two or three years before the label started. And so they started to feel there was this huge amount of music which was unknown, and could maybe be interesting to record on a physical format, instead of just putting on shows.

And so, through Marfox, we came in contact with this music. The first record we planned was always going to be a DJ Marfox record, there was no question about that. We wanted to capture the chain of respect that was already going on, that was independent from us, and DJ Marfox was the guy everyone in the scene looked up to.

So, you mentioned trust. Well firstly of course when Pedro and Nelson approached Marfox, it was really strange, because there were these two white guys going to the neighbourhood, talking about my music, as Marfox tells it: “These white guys with long hair, what do they want? Do they want to exploit me? It was strange.” But with patience and an open heart from both sides, everything was really easy to put together. Marfox is really an easygoing guy, and he knew perfectly what he wanted for his music – he saw in this an opportunity that he was already looking for. But it isn’t easy for some guy from the neighbourhoods around Lisbon, white or black, no matter, to break out into the main dance scene, in the city firstly, and then outside.

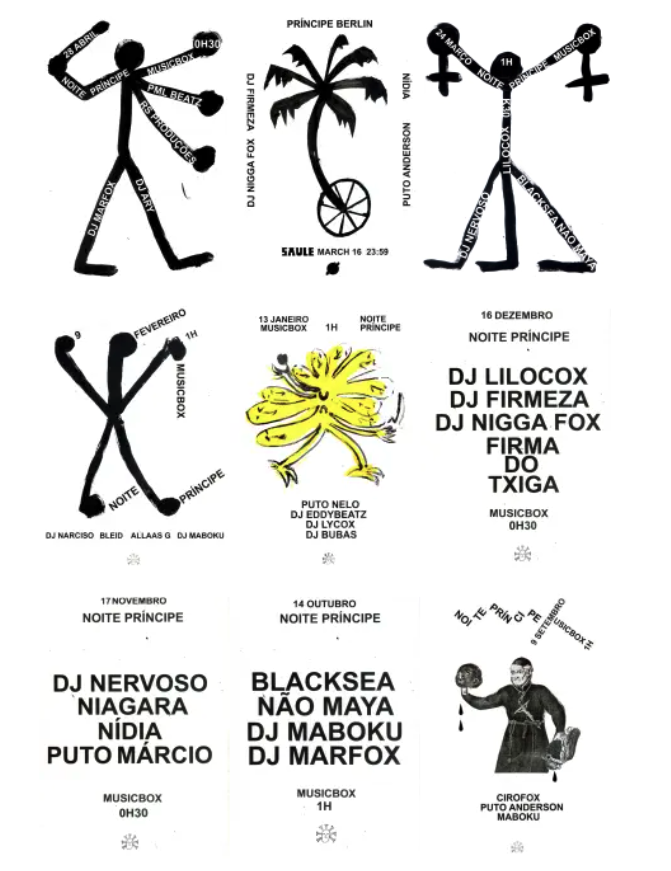

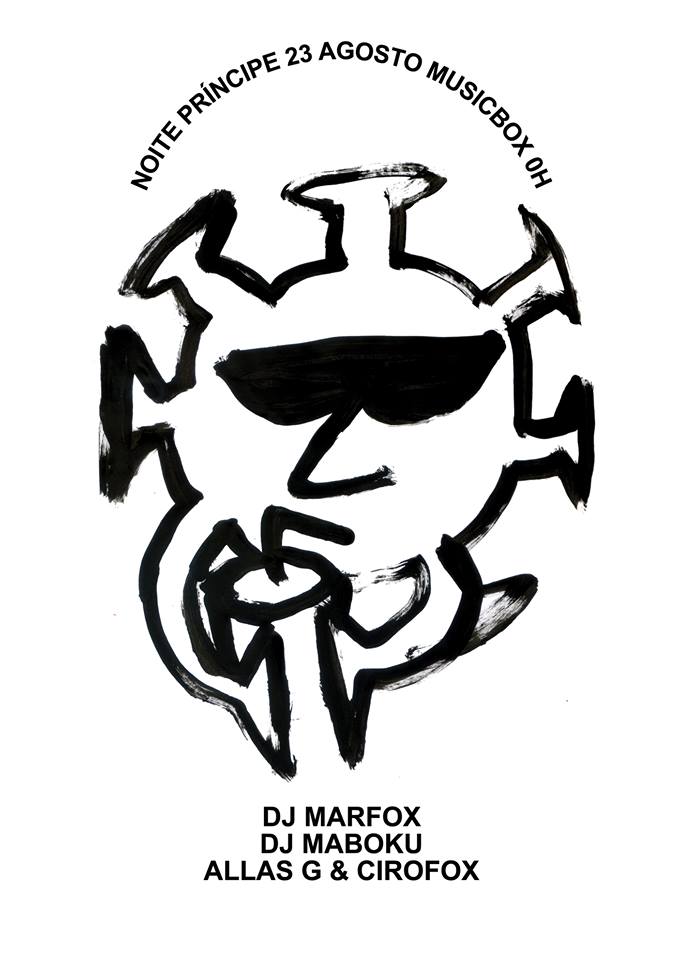

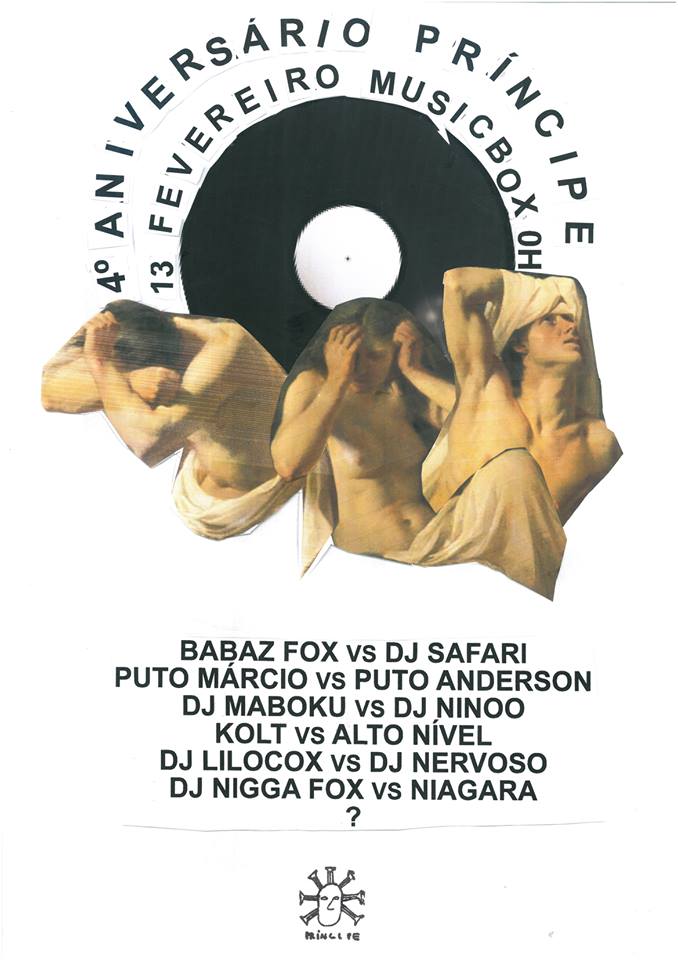

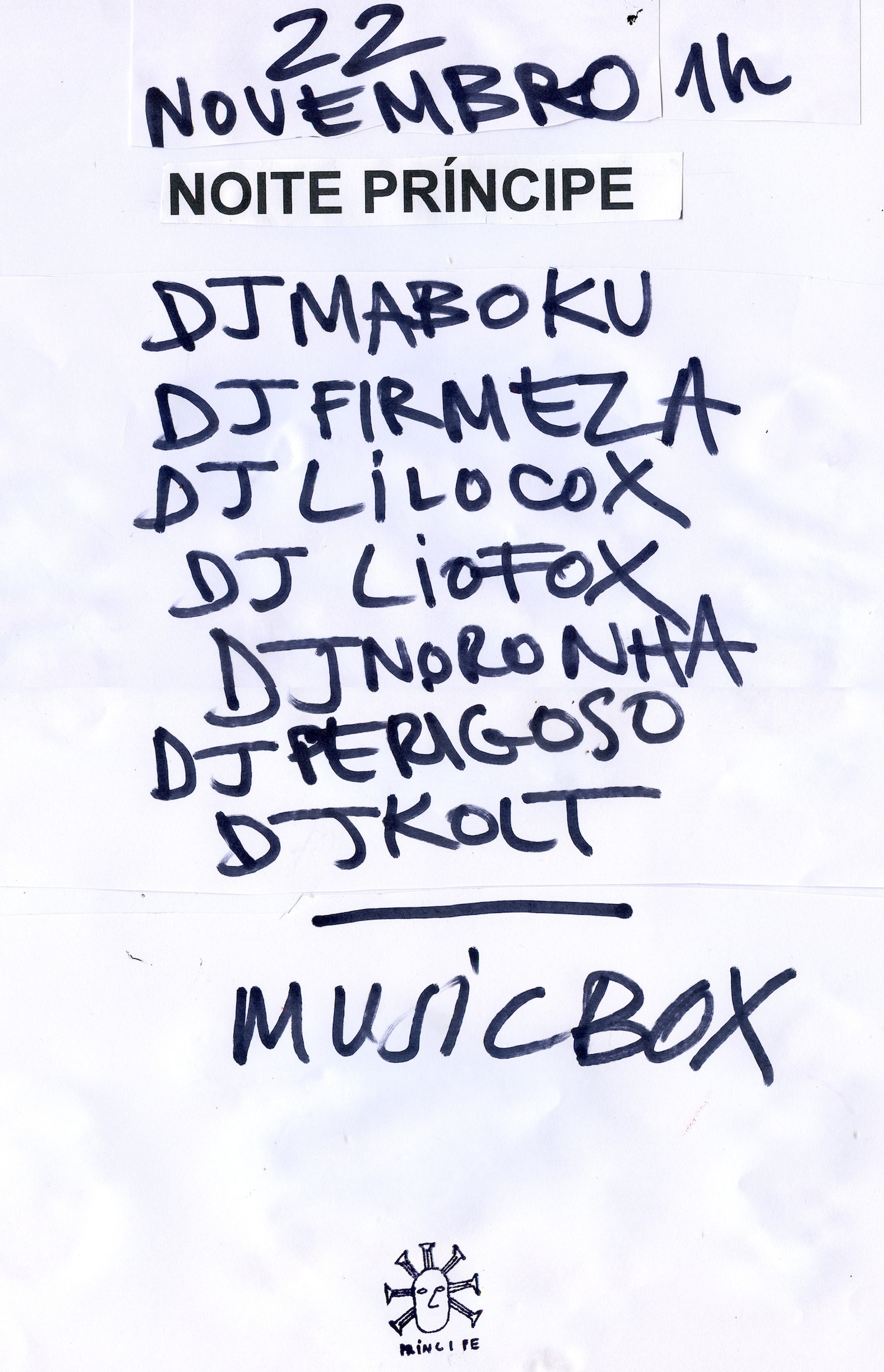

You’ve been running a monthly residency at Musicbox club since 2012. How important has having a physical club night been to creating a community around Príncipe?

JM: Even before the label started, we’d planned to show this music live with a club night. We found Musicbox, and we decided to start there with a monthly residency, and with that residency one of our ideas was to bring out other producers, to show their work live. We encouraged them to play their own music as much as possible, and not try to be commercial, not try to dilute their personality playing other music that was just to fill in a DJ set.

So the Musicbox night quickly became, certainly a showcase for new talent, even for us, because we could see who was really good as a DJ, who was better as a producer, and they themselves could feel what they were more comfortable doing; either DJing, producing, or both things.

By meeting them personally (which was always our idea when thinking about creating a local label) we can meet eye to eye, we can talk, we can discuss things, and from there we can build trust. So the club night was absolutely crucial in building that trust, a sort of family grew from there.

The Musicbox night quickly became a showcase

We tried to nurture the more dedicated group of producers, and we started looking out for more talent, introducing new kids to the downtown city audience. They were not used to playing in the city centre, and so it took some months, also, to be able to transform the night into a more plural experience, with friends, girlfriends, boyfriends, from the neighbourhood, coming along to support the DJs. That took some time, instead of mainly a white audience. We had to wait a few months to see the club as a more plural experience, and the experience we imagined in the first place.

Can you talk a little bit more about the kind of experience you imagined the label as in the first place, then?

JM: Well for us, it’s always about music. So, first and foremost we have to like the music, we have to believe in it. That’s how it started. And then, secondly, we have to feel the music needs us, and doesn’t have its own channels to reach the world. We could easily release other stuff, maybe more straight techno and house which is being made in Portugal, and some is really good, but then we thought: do they really need us? Because there are already a ton of techno and house labels out there. So do they really need us? What difference are we going to make with this music? This could be produced either in London or Paris or Berlin or Lisbon, no matter. It has no distinctive sound to it.

For us, it’s always about music

This music needed someone, and it happened to be us. This music needed someone to help it come out of the neighbourhoods, out into the world. First into the city, which was always our first idea – to do something with local music, and for locals.

Building a community was not our first idea, music was the first idea, but quickly we understood that we couldn’t just be that kind of label, who asks for music, selects it, releases it, and then doesn’t really do anything else for the artists. We quickly understood that this was a social thing, instead of being just a record label we had to do something else. We had to get involved in a different way, more humane, and more socially aware, and this was really clear to us once we started working with the artists. For example DJ Nigga Fox was three times denied entry to the UK, before his first appearance there, because he’s Angolan, and although he’s lived in Portugal for years he couldn’t get a visa. And so we also had to take care of those issues; helping get visas, social security, all that kind of stuff. Sometimes even paying some debts, I’m not exaggerating – fortunately it was not the rule, it was always the exception, but it happened.

I was going to ask what you think the role of the independent record label is, but I support in this instance it’s a social net almost?

JM: Yeah but the beautiful thing to us is that it just happened that way, we didn’t plan it that way. We didn’t set out as, “Oh! Let’s be socially conscious! Let’s pick up those kids who really need attention!” No, it wasn’t like that. The beautiful thing is we just realised we had to work like that, during the process.

I think it’s not in the nature of any of us to do that deliberately. So, music is always number one, it’s the first motivation always, and then, whatever happens next comes from the music, from the love of the music.

What have been some of your defining moments over the past decade?

JM: First of all starting the label, and it becoming sort of political without trying to be political, just the fact that the music was being released and exposed to a wider audience, especially in the centre. It’s maybe more difficult to establish this music in the centre of Lisbon, and Portugal, than internationally. So it was political right from the start.

At the start, the first two records were not really selling that well, because this was so new, and because it didn’t have a context we had to create a context from scratch. We already had the residency at Musicbox, and they were really crucial in helping us release number three and four in the catalogue; they contributed financially for both releases. Musicbox was really instrumental in keeping the label going, for a while, that was in 2013.

Later that same year, Marfox and Nigga Fox played at Unsound festival in Poland, and it happened that a lot of big names from the industry and press were there. From October 2013 onwards, gigs started to multiply, and that was really a defining moment, that was a turning point, for sure.

The other big moment, aside from DJs breaking in America, was for the label to be able to establish a regular gig circuit for the main DJs, and get them to live from the music. None of them lived from the music, they all worked, or studied, or were unemployed, so though this wasn’t really a defining moment, it’s a major point in the life of the label, to be able to give the opportunity to a few DJs to live from their music.

Things always moved slowly, and according to our own personal lives, so the label was always slow in moving on, and then the pandemic came, and we were fortunate to be able to release a digital only compilation, where all the money went to the artists. The way we were able to put it together in like a week amazed me, and made me really happy. The way the artists responded, the way we quickly selected the music, and the way the money was able to be channelled directly to the artists, it made me really proud.

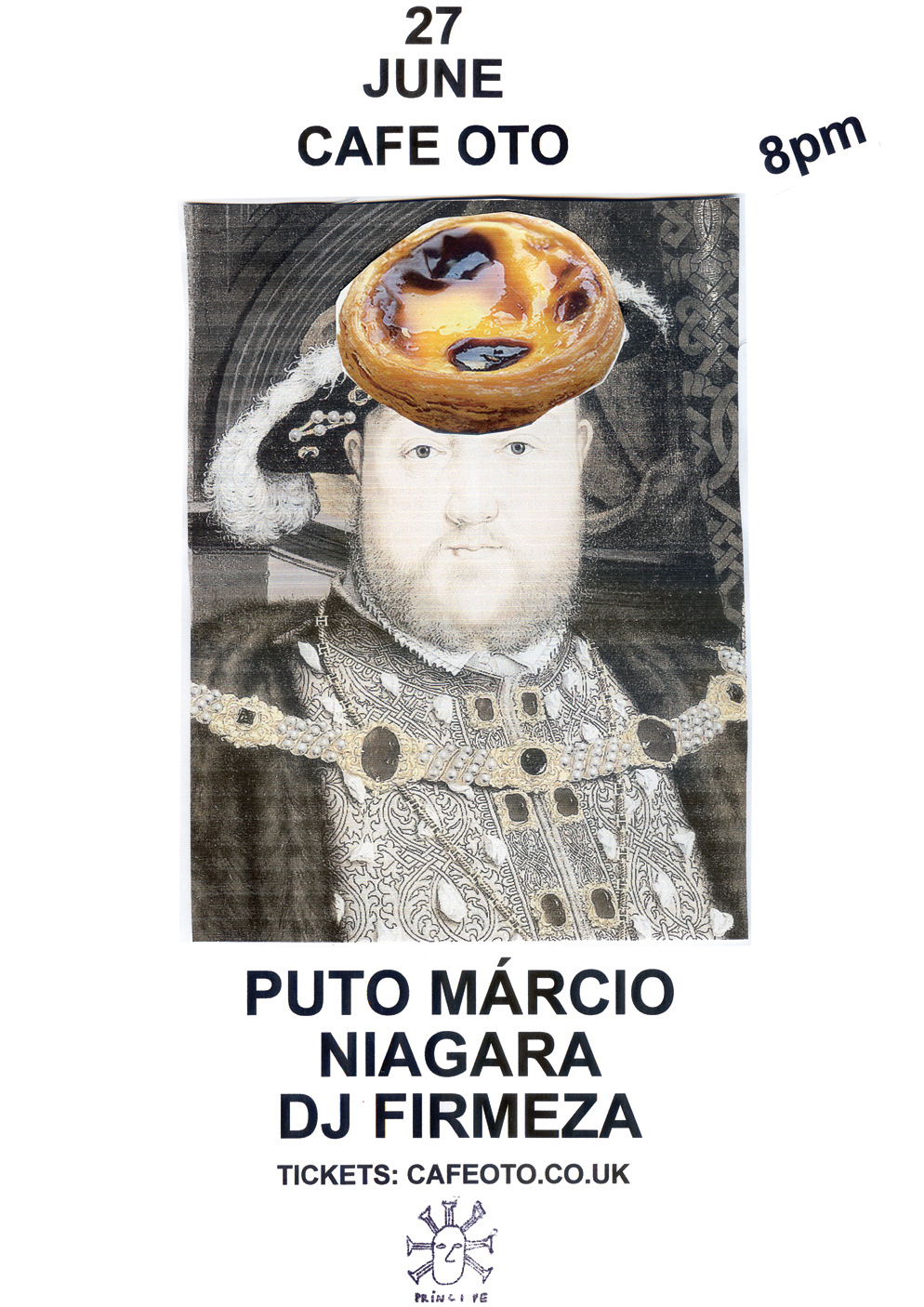

Marcio Matos creates your label artwork. How important do you think the visuals have been in carving out a distinct identity for the label?

JM: Very important of course. The idea was always to produce the sleeves locally, not printing them at the plant where the records are produced. And so the obvious thing was for the covers to be hand-painted, and Marcio very much wanted to do that. Of course over the years, when you think about hand-painting 500 copies of a record, five or six times a year, that’s not very comfortable. You can imagine 500 copies left to dry in a city apartment, along the corridors, bathroom, and all the bedrooms, on top of the bed, for a whole day.

The idea was always to produce the sleeves locally

From the start this was an important message we wanted to convey. Painting a sleeve, which then goes out to the market and reaches people, there’s some kind of arcane, ancient sense of direct connection, when something is handmade, and reaches the final consumer. Call it outdated, but it can make some difference.

What does the future look like for Príncipe?

JM: I think it’s looking bright, to be honest. These two years were strange, not only for us of course, for everybody, especially in the music scene. For a while we didn’t really know what would happen, especially with a live circuit being the main source of income to most of the DJs and producers we work with. I think it would be near impossible to guarantee a livelihood to the DJs with just being a label, so it’s a big relief that things seem to be starting to go back to normal, with live dates being booked.

We feel there’s a renewed interest in the label too, and it didn’t disappear from people’s minds and hearts, which we were kind of afraid of, because we practically didn’t release anything in these two years.

We were afraid that as things always move faster and faster, that people would forget and something else would come up, that would capture people’s interest. So we were very happy to find out that people are still interested. DJs are being booked again, and we have a ton of new releases prepared, because if anything we’ve had time to go back to the archives and take another listen to the ton of music we already have on our harddrives, and plan, for example, two commemorative releases. We wanted to put them out last year and early this year, but the plants are all so delayed in production that we don’t make plans anymore, we just hope to be able to release them at some point this year.

Read More: Creating A Neighbourhood With Radio Alhara