How do you think growing up in Beirut has shaped your work?

I grew up in quite a particular context, and a relatively unusual setting for my surroundings. I grew up with two artists for parents, which I guess is unusual anywhere. My mother is a painter, and my father is a musician who also studied theatre and had an acting career when he was younger. Then also, during the Lebanese Civil War, both of my parents were part of a children’s puppet theatre troupe. My house was constantly filled with my mum making puppets and my dad composing music.

I read that you were a child actor too?

I’ll tell you the trajectory because funnily enough, it wasn’t directly because of my father that I started acting. It was a really creative atmosphere: mixing music with theatre and text. So it’s no wonder I grew up with a creative flair. The acting kind of happened randomly – an actor friend of my dad’s was visiting us, and he had just gotten a role on this period drama. They were looking for the kid of that family, and he saw me – I was very much a theatrical person, putting on a show for whoever would watch – and so he said, “I think your son should go and audition for this role.” I don’t think anyone needed to push me. I just needed someone to say, “Do you want to?” and I was all in.

There was charm and beauty to the chaos

Circling back to your first question, in terms of Beirut more generally, I do remember being very young and in the car with my parents, and I would just look at shop signs and read the signs, look at the fonts and the colours. From a graphic design point of view, shop signs were very alluring to me.

I mean, you had Arabic ones, you had English mixed ones, old school ones, modern ones. My childhood was a city emerging from war. It was chaos and mess, and everything goes. It’s not like everything was very tidy and disciplined. It was very chaotic but there was charm and beauty to the chaos, to a degree.

And was there any other early sign you’d pursue graphic design?

I remember my brother went into graphic design and downloaded Photoshop on the home computer, and that was it. I would just be on my own, learning, and my favourite thing was to montage cutouts of my family members with the heads of celebrities. My grandma was Beyoncé! They’d all send me requests.

When it came time to apply for university I had three applications: acting, graphic design and psychology. Imagine, psychology! My dad said, “I studied theatre, and you know how terrible it’s been trying to get on my feet. You have an acting portfolio that you could still develop in a personal capacity, but do you want to put all of your eggs in that box? Or do you want to try to just have something that is a bit more flexible?” I thought, no, I don’t want to redo all the struggles you went through, I want something a little more secure, and that was my route to graphic design. What I would say is that I have spent years trying to take graphic design apart, not in a bad way, but to start to bring in all of those early passions of mine: storytelling, performance, theatricality, communication. Because I enjoy doing graphic design per se, but I think to me, it gets exciting when other things start to enter.

You often make work with a political message, and you’ve gone viral for Instagram posts in support of Palestine specifically. Do you think designers have a responsibility to be politically engaged?

I would say yes. Obviously that’s a personal opinion, but it also relates to the First Things First manifesto, which was originally done in 1964, and then redone later on in the ’90s. It was a group of designers at the time, who were so fed up with graphic design being completely dominated by big idea advertising. They said, “That’s fine. We understand that there’s a need for this, but at the same time we have all of these brilliant tools to communicate, and we have a duty to also use those skills for the greater good of our communities and societies.” I grew up very much in that school – the school that I went to in Beirut, the American University of Beirut, the design department really encouraged creating work that has political and social elements.

I’m someone with very firm stances and principles

Personally, I’m someone with very firm stances and principles, so it’s going to be very difficult for me to divorce these things from my work. Then what reinforced that is when I moved to London, I ended up working at Barnbrook, Jonathan Barnbrook’s practice, which has historically been known for creating work that has a political nature, and working on non-commercial projects and socially conscientious projects. So it was the natural route for me to continue thinking that way. Whether it’s the purely political work that I share on my personal Instagram, or Takweer, for me these all fall in the same category. With my work, sometimes things are not obviously political, but there’s always something political there that I’ve slipped in. I am always thinking: “I’m going to use this as a vehicle to make a statement.”

There are many ways to be political as well.

Exactly. It’s also about saying no to certain projects: I’m not going to give you my skills because I don’t believe in what you’re doing, or I think what you’re doing is wrong.

And when it comes to projects you don’t work on, how do you draw the line?

I think we all need to define where our red lines are; and they vary from one person to another. Some people are very extreme, for some people the red line is almost not there. For me, yes, I understand that, especially living in a city like London, people need to survive. I have a certain set of principles that are untouchable, and then there are other things where the grey area could be engaged with a little bit more.

If you want to really go into it, every museum has questionable funding, every venue has questionable funding, every artist has performed somewhere that might have a question mark. So you need to have principles, but to also be reasonable.

In an age of activism on social media, what role do you think design has in spreading and shaping political messages?

I think we are definitely in a better position than pre-social media, because we have a massive number of people fixated on their phones, and the phone has become a source of information and content. So obviously, as with everything within capitalist society, this has been mainly used to sell people stuff, marketing and targeted ads etc. But what if we hijack these tools and try to take advantage of the fact that all of these people are glued to their phone to spread another kind of message? Obviously, Facebook is doing this with fake news, but what if we do it in a way that could help shape people’s opinions about a subject matter that is currently distorted in the media?

What if we hijack these tools?

This is where, for example, my work specifically with the Palestinian cause comes in, because I felt that I had a large audience, a lot of whom were Arab and informed about the subject, but the majority of whom were Westerners or non Arabs, who are not well informed on the subject, and who need to be armed with the right kind of language to be able to debate. I thought, I’m a graphic designer, my job is to create visuals that are able to communicate. I also have a way with words, and with editing text and content to make it impactful, and I have the knowledge of the subject matter to a degree. If I put these materials together and create something shareable, something digestible, then I could be onto something. I didn’t really understand the extent to which those posts from 2021 would have, and it was like wildfire. I felt like people were suddenly emboldened because they’re thinking, “We want to talk about this. But we feel we didn’t know what to say.” So I said, “These are your tools, you could use them to your advantage.”

If you want to read a book or a longer article, do it. But within the context of social media, it has to be short, to the point, but it should still have all of the content and the context needed to understand a complex situation.

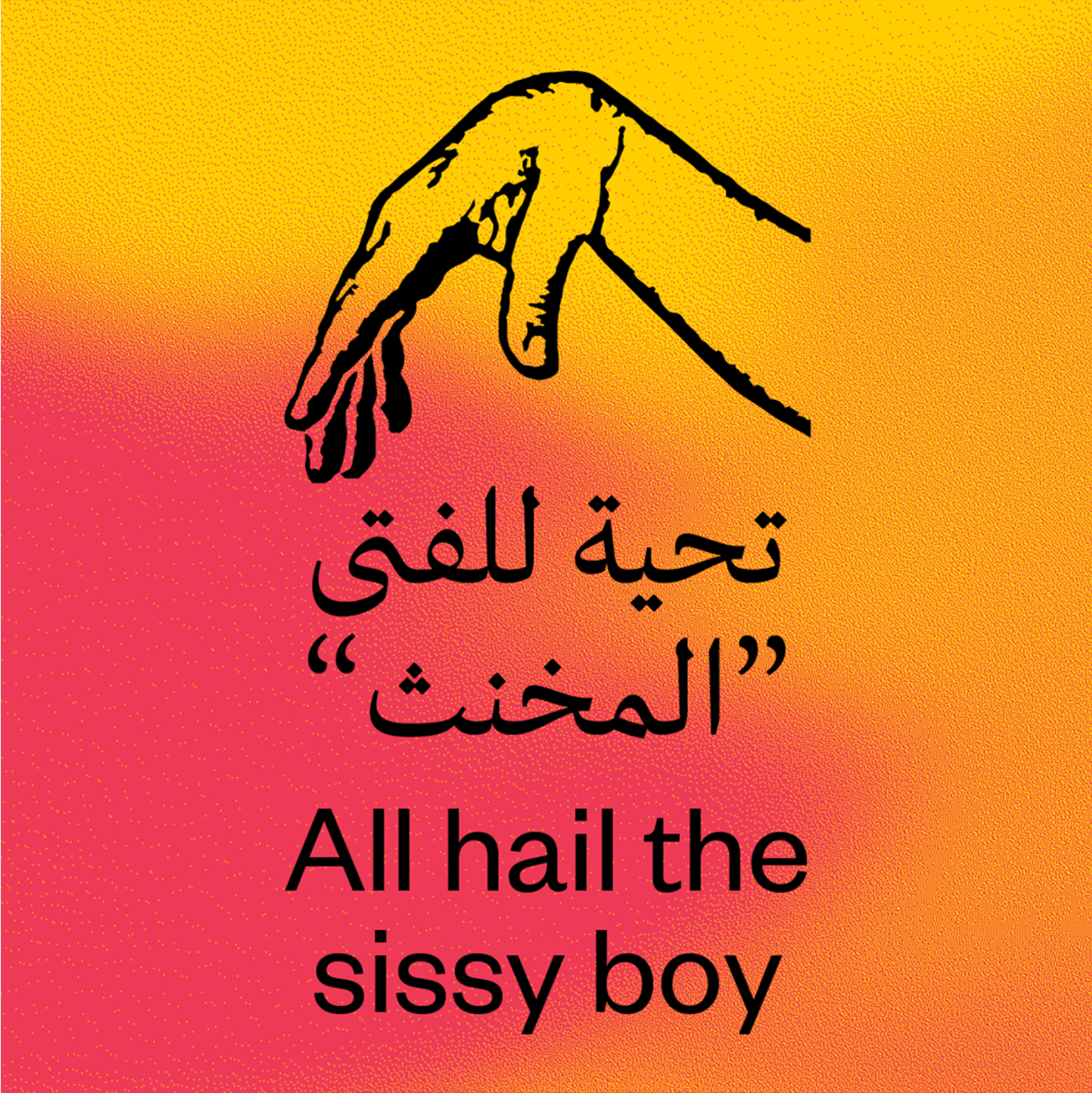

You launched Takweer in 2019. Can you talk a little about your early motivations? And what did you envision for it when you started out?

I’m queer, I’m Arab, and of a Muslim background, although not practising. I’m fortunate because I come from a family that’s progressive. I had parents who were well informed and had queer people in their lives even before I existed, so they knew that this was not just some sort of alien existence, this is part of life. So coming out to them, even though it didn’t happen in that straightaway of a manner, was okay. It’s always a work in progress, but it was more, “Let’s address this situation,” rather than a big drama. That helped me be in touch with my queer identity and not feel it was this shameful thing, however it was really only in London where I could express myself in the club, in the streets, without having to pay too much attention to my surroundings.

I worked at Barnbrook for seven years, and I loved it there. It was a dream job. But it got to a point where there was a lot of frustration on my part that I was not able to make work about things that mattered to me on a personal level. Whether that is projects that are in Arabic, whether that is something that has to do with my culture, or that has to do with my identity as a queer person.

This is where the seed of Takweer started to bubble up. Originally it was folders on my computer where I would just collect stuff, I had a very short lived Tumblr too, and I actually came up with the name two years before I launched. At some point, I thought, “Stop waiting. Just put it on Instagram, that’s a language you are familiar with.”

For a platform that began as something digital, why do you think having a physical publication is important?

The Instagram page was only ever meant to be a broad exploration that would create a launchpad for focused projects. The book is the first fully realised project.

The page is very broad. There’s music, cinema, literature, poetry, memes and whatever. This book takes language, dialect, and queerness, and then tries to explore it to the maximum. This book started as kind of a lockdown project. I had just quit my job at the worst time possible, so I thought, “Alright, things are falling apart. But let’s come up with a job for each day.” I used a submission form on Instagram and asked Takweer’s followers, “What are the words or terms that you as an Arab individual, an Arabic speaker, know of that are connected to your queerness? And those can be good words, bad words, endearing or derogatory, said by members of the LGBTQ community, or possibly being hurled from the outside – anything goes. What are those words?”

This book started as kind of a lockdown project

I started to get the submissions, and it was a lot. I thought, “Whoa, I thought I knew them all.” But then I realised, when we say the Arab world it’s what, half a billion people? Living across a massive piece of land, and of very different cultures with wildly different dialects. So I started to explore this amazing linguistic landscape, and this is where the glossary came from; trying to accumulate a glossary of the linguistic landscape around queerness within the Arabic speaking region right now.

The more I learned, the more ambitious the project became. At first it was a cute little glossary, then I realised that, “I have 300 plus entries here!” Then I felt we could bring in visual elements, so I commissioned an illustrator to visualise some of the more graphic terms. I invited nine writers to reflect and write essays about language dialect translation, queerness, and so the project expanded and grew organically.

For this project I went with language, and it’s not a surprise, because it’s something I’m personally interested in, which you can see in my work; there’s a lot of language and text is always at the forefront. But I already have ideas for other projects that might take the form of an exhibition, or an artist book or a video piece. So the idea is that it’s going to be very multidisciplinary.

Read More: Storytelling With Ismaila Rufai