On Shifting Perceptions Around Burnout, Depression and Anxiety

Stephen Heffernan: Definitely my relationship with these things has changed, and has become a lot more positive. For a long time I would have been nervous to admit to ‘weaknesses’, because I think in the creativity industries, every time you talk to a client or are meeting someone, you have to be on really top form. And the feeling is that, if you’re not, you might lose that client, so you’re always in ‘impress’ mode. It’s sort of a thing that no one talks about, that your personality has to be on all the time, and that’s in terms of posting stuff on socials, pitching, all of it.

It’s starting to change, and I think it is going in the right direction. But it’s a strange job and industry; it’s very much that you’re trying to impress people every time, because if you don’t you may never see them again.

Faye Hickey, PoetsIN: I think being on the grind can sometimes be glamorised, over time I’ve realised that that’s not productive in the long term. So I suppose it’s about breaking through that ‘work hard/play hard’ mentality and actually looking after yourself, and then you produce better work.

Bora Murmure: I relate to what you both said, definitely that it’s a strange industry. In my work I often try to unravel emotions and dig into them, and to open a form of acceptance to emotions. So it’s kind of weird to be contacted professionally by people who want your artistry, which is based on realness and trying to be aligned with who you are through the fluctuations of it.

Your personality has to be on all the time

The way it shifted for me is to try and accept my hypersensitivity, and not minimise it or hide it, because I’ve been ashamed about ‘feeling too much’ my whole life. Also, I think we are often made to think that being professional is about not being emotional, and that makes it difficult to be yourself.

Georgina Johnson: I completely agree with you about being socialised to think that being professional can’t be emotional. It’s interesting because creative work is often deeply emotional, and very personal, so it’s hard for feelings and personality not to bleed into it.

Hannah Carlile, KesselsKramer: It does feel highly personal, and so when a fail comes along, which inevitably it does, it feels like you personally have failed. It’s really hard to find that separation between yourself and your work.

Stephen Heffernan: There’s also the fact that you might be creating something, and you think, “This is the best thing I’ve ever made!” And you’re so proud of it, but it’s not necessarily seen that way by a client. Certain projects you do get really invested in, you’re like, “I’ll put so much of myself into this.” Then if it ends up getting canned it can feel very personal. You learn to take it on the chin, but it can be very hard, even after years, to not take something personally, because a lot of the time it’s a case of, “Well I really like this. I think this is great, and I don’t know why you don’t.” It’s funny, you don’t want to get too numb to things and be completely emotionless, but then you also don’t want to be erratic or too angry when someone says no.

It’s not always about the extreme

Georgina Johnson: I think that word choice is really interesting – ‘get erratic’ – because what does that even mean? I think often when we do talk about mental health, we tend to speak in extremes. Sometimes it can just be a lull, you can be in a place where nothing happens to you, nothing comes to you, you don’t have the emotion, or the capacity to build something. It’s not always about the extreme, and I think using those terms can make it difficult for some people to characterise, or to know, when something is going on. Maybe they think it doesn’t look as ‘bad’ as it should, in terms of how it’s characterised in the media or the narrative that’s spread around it.

On ‘Healthy’ Relationships To Work

Bora Murmure: I don’t know if my relationship to my practice is healthy. The way that I try to deal with emotions in my practice is to not judge them, and not have a binary vision of, some are good and some are bad. So I guess the word ‘healthy’ in itself feels like pressure on me. I think overall I’d say no, I don’t necessarily have a healthy relationship to my practice, but in a way it is getting more and more healthy, because I’m trying to build acceptance towards what I feel.

On the days that I don’t feel good, I’m trying to do the best I can to be respectful of what I feel. And especially with art, it’s difficult, because you feel like if you stop creating, even for one day, then you’re going to lose opportunities. It’s such a big, constant pressure that I’m trying to take at least 15 minutes of meditation every day, not in a pure sense, but having my own little rituals to kind of check in and see if I feel like I can create or not. I don’t know how the other creatives feel, but for me, art is, it’s my job, of course, but it’s not only my job, it’s part of me. So I’m trying to handle it with care as much as I can, so as to not wreck it.

Georgina Johnson: You touched on something really important there, about using binary language, because when you say ‘healthy’, then the opposite of that is ‘sick’. But if you are dealing with a mental health issue, there is so much in-between, and binary can become unhelpful.

Stephen Heffernan: Day-to-day it’s super fulfilling, especially when things go ahead, but it can also be really hard to take the bad parts. A competitive bit of fear is a healthy anxiety, almost, and things like deadlines can be a really good driver. But it is definitely about finding a balance.

Hannah Carlile, KesselsKramer: My mental health in terms of my creativity is a bit of a work in progress. It’s not 100% healthy all the time; even making this exhibition was quite a stressful process, which is super ironic. But I’m learning to put the laptop down at six, and to feel comfortable with the fact that my best is enough. I think we’ve touched on having some time to go inwards – having a moment of tapping into how you feel is really important, and just having a bit of a break too.

A competitive bit of fear is a healthy anxiety

Georgina Johnson: In terms of extremes, I know exactly what you mean. Especially when you want to meet a deadline, it can become, “Oh, my God, I need to put my life, my blood, the eggs I have in the fridge, everything needs to be in this.” It’s not helpful for anyone; I’ve gone through periods where I haven’t slept, even.

I think a lot of it is about understanding where growth is, and what you characterise as growth. Is accepting every project necessary? Is being productive every moment of the day necessary? What does a balanced life look like? Do you go for walks? Do you drink water? Are you kind to yourself? Bora, you touched on so many important points about just giving yourself the leeway to have these emotions, feel them, and understand that they come and go.

On Being Open About Mental Health:

Hannah Carlile, KesselsKramer: It’s hard. We’ve created this weird connection between burnout and weakness, and I think there’s fear in speaking out and coming across as being not good at your job or not good at what you do. It feels like there’s such a high barrier to having that conversation, and obviously, if you don’t have the conversation you can’t solve it.

Stephen Heffernan: I’m completely freelance currently, and every client that I have I speak to and handle directly. I’ve noticed that as a bit of a stress, I have to really be on top form all the time, every time we speak. And say if they’ve got a really hard deadline you kind of have to be in that role of, “Oh yeah, of course! No, that’s no problem whatsoever!” And in your head you’re just thinking, “Okay I’ll just have to be up for the next 20 hours or so.”

My fear was always that if I said no, a client would automatically turn around and say, “Okay, we’ll give it to someone who can do it.” But what I’ve noticed is, nine out of ten times, they’ll say, “Okay, cool. It’s not super urgent, we can push that back, how long do you need?” I’ve noticed that being more honest and more open about it, and being able to say, “That’s just not really feasible.” I think a lot of the time people are open to it.

We forget that everything is impermanent

I guess with setting boundaries for work, you can almost feel like you’ve given up a little bit. But a lot of the time it’s more this psychological thing, where you brick yourself into this very high pressure position that doesn’t necessarily fully exist.

Joe Watts, PoetsIN: One thing I’ve noticed is that opening up and creating safe spaces really does have a huge impact, especially with the people we see over time. Allowing people to talk really does help and have a positive impact.

Bora Murmure: Personally, what has been the most challenging was the fear. Because I guess as humans, sometimes we forget that everything is impermanent, and that we change every day. When I speak now, I’m not going to say the same things tomorrow. I think what has been a hustle and a struggle for me as an artist, and also in my personal life, is this fear of being boxed into something by what I say. That’s also been the fear I had for so long, in terms of sharing about my mental health with others, because I didn’t want to be frozen in an image that I had shared at that moment.

On What Could Make Openness Easier

Hannah Carlile, KesselsKramer: It’s probably different for freelancers, but working in a studio, I think it can really help when that message comes from the top down – when your boss or senior gives you permission to take a break. Something that we do at KesselsKramer is have a section on our timesheets blocked out for ‘Feeling Well’. That’s a moment to take a break, and go absorb some inspiration. I think just having that formalised time to yourself really, really helps.

Stephen Heffernan: Even for yourself to take a step back after a stressful project, when you do feel okay again, because I think often when you look back, you don’t really remember the bad, you just think, “Oh that was a super successful project.”

So I think sitting down after the fact and saying, “Well, this person who worked on it really wasn’t helpful, they made it 10 times more stressful.” Or, “I do this thing that I could stop doing which would make it all go better.” It’s a really hard thing to do, especially if something is a success after you finish it, the temptation is to say, “Oh it was perfect.” I think it’s good to try and pick your successes apart.

Try and pick your successes apart

We all dig holes for ourselves all the time with work, and it’s just about figuring out how you do it; maybe you’re a people pleaser, you might take too much on, whatever it is. Then it’s about stopping yourself from getting there.

Georgina Johnson: I’ve just finished this Curatorial Accelerator programme with the arts funder Jerwood Arts, and I learnt so much on it. We went to lots of different places in the UK to learn about the different arts ecosystems, and how these huge institutions work with climate groups, disability groups and others. What I found really interesting about the conversation around disability, and mental health within a disability context, was that some specific groups embedded this thing called a, ‘care’ or ‘empathy’ contract.

So within their accessibility document that they send to a client, they’ll include this contract that essentially outlines their boundaries, pretty much from the jump: “You’re coming to me for this work, so this is what I’m sending you, and this is the way that I intend to work with you. You can’t email me after a certain time, I’m not going to baby you…”

I found that really radical, and it’s something that I want to do and something that I would definitely encourage anyone to do. Let people know upfront that these are your boundaries and have a back and forth about it – how you’ve worked with other people, what hasn’t gone well, whatever it is.

Bora Murmure: I’ve had bad experiences in terms of emotional relationships during projects, so I worked on this document that I now send out any time I get contacted. It explains how I work, what my character is like, what my boundaries are, and I think this helps a lot. I was scared to send it at first, but it helps on both sides. Communication is very important, and by doing this I opened up a much clearer communication on both sides, and it ended up making the working process go a lot quicker too. Also, at the end of the document I always leave a blank space for the person that I’m working with to put their own comments, or reply, so that we can have a chance to talk about expectations on both sides, and it works every time.

On Coping Strategies

Stephen Heffernan: I think when you start off working in an industry, you are in ‘impress mode’ all the time. It does often take someone senior to say, “You don’t have to do that. We know you can do your job. You don’t need to be here from 10am until 10pm every night.” It’s good to have someone to tell you that what you’re doing is okay, because it takes a while to verify yourself.

Georgina Johnson: It’s also just economics. With freelancers especially, because it is such a precarious position, you do end up taking on everything and accepting everything, and you will feel the pressure coming down. It’s very hard to compartmentalise the different clients and the different modes of communication, but I think having good communication and a bit more openness can be really critical. I think that can come from being a bit more discerning with the type of people you want to work with as well.

Communication is very important

Hannah Carlile, KesselsKramer: I think a good mode to get into is to think of yourself as if you’re speaking to somebody else, which ties to this idea of getting permission from somebody senior to kind of settle your worries. I think sometimes you can give that to yourself, if you just take yourself out of the situation, and look at it with a bit of perspective: “Oh, actually, I do deserve a bit more time and I am good, valuable. I’m going to send this email requesting for more time or whatever it is that I need.”

Joe Watts, PoetsIN: I am rubbish at looking after myself, although I am getting better at recognising those signs and putting those things in place to support me. Sometimes it is as simple as taking time to pause and thinking about what you are capable of doing.

Bora Murmure: One of my best friends is dealing with very heavy mental health issues at the minute. At the beginning I wanted to understand so much that I was asking loads of questions. I was so scared of not being able to help him and not being a good friend, that I was inadvertently putting pressure on them. One day, they just told me, “No, you don’t have to understand me and what is happening in my head, in order to be my friend.”

That really helped, and humbled, me. I was like, “You’re right. Maybe I can’t understand you and maybe I will never know what it is to be you. But at least I can try my best, so you know that I love you and I care.” So yes, it really humbled me to hear that, and since then my perception on others has really changed. Before, I thought that I would need to feel everything that the other person is feeling in order to love them or to understand them. But I’m not them, so I don’t need to do that.

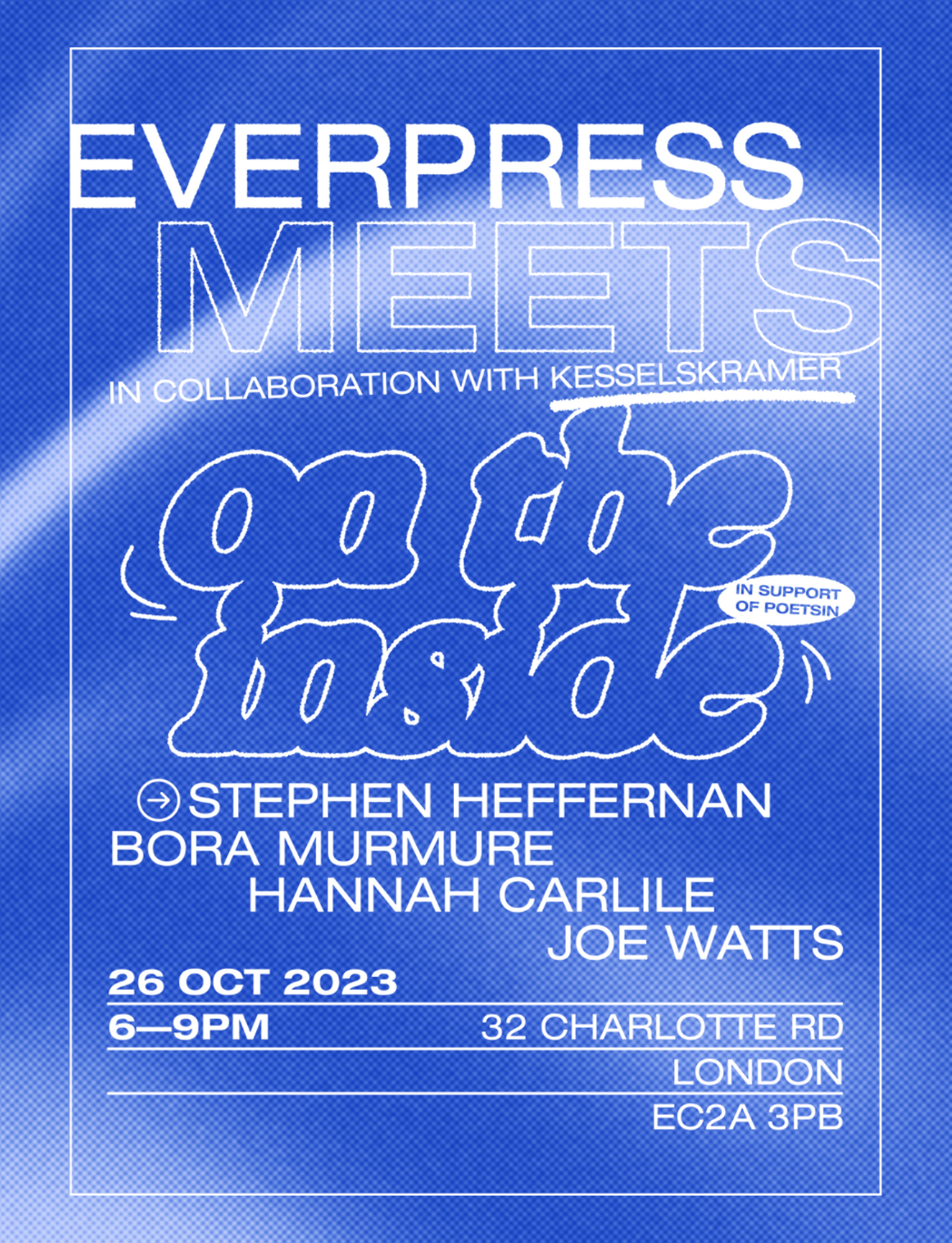

Read More: What We Learned At July’s Everpress Meets