Is it possible to earn one’s own seat at the big boys’ table, as a woman, not by laughing along at your degradation, but adopting all that gung-ho, big-boy violence for oneself? Culturally, there is something shocking in the image of a woman choosing to destroy what is supposedly — which is to say, misogynistically — her most valuable asset: her own flesh. If seeing the inside of a good-looking blonde woman on the internet no longer holds much shock value, it is arguable that some shock remains when that inside is the inside of her left arm. Paige Ginn, a sunny, pretty, leggy girl from San Diego, has achieved renown online for faking violent falls in very public places — at In ‘n’ Out and at the mall, at Walmart or the bowling alley — in a way that alarms and delights her fans in equal measure. On May 26th, 2016, she shared a photograph on Instagram of the skin stripped from her forearm by a treebranch, the interior of her body flashing crimson. “Bush: 9,273,280 Paige: 0,” she wrote in the caption, perhaps more casually than one might expect given the severity of the injury, adding: “#Timeforlifeinsurance.”

As with Johnny Knoxville, Ginn’s obvious attractiveness is intended to add seasoning to the joke; both of them toned and tanned and enviable opposite sides of the same hot coin. In a clip where Ginn falls helplessly inside a laundromat, her perfect legs fly out akimbo like a Barbie being used nefariously by a perverted, precocious five-year-old; on the beach, she flings herself out of a boat and onto land in booty shorts so minute that the end result resembles a cross between a Crossfit ad, a skit performed by Buster Keaton, and a pornographic take on Hans Christian Andersson’s The Little Mermaid. In the In ‘n’ Out-set clip, she coordinates her outfit and her wig to the ketchup-and mustard colours of the outlet’s famous logo, making herself an eye-catching logo, too — a capitalist symbol and a piece of living pop art, maybe unwittingly drawing parallels between the casual consumption of white girls who might have been Sorority sisters, and the casual consumption of fast food.

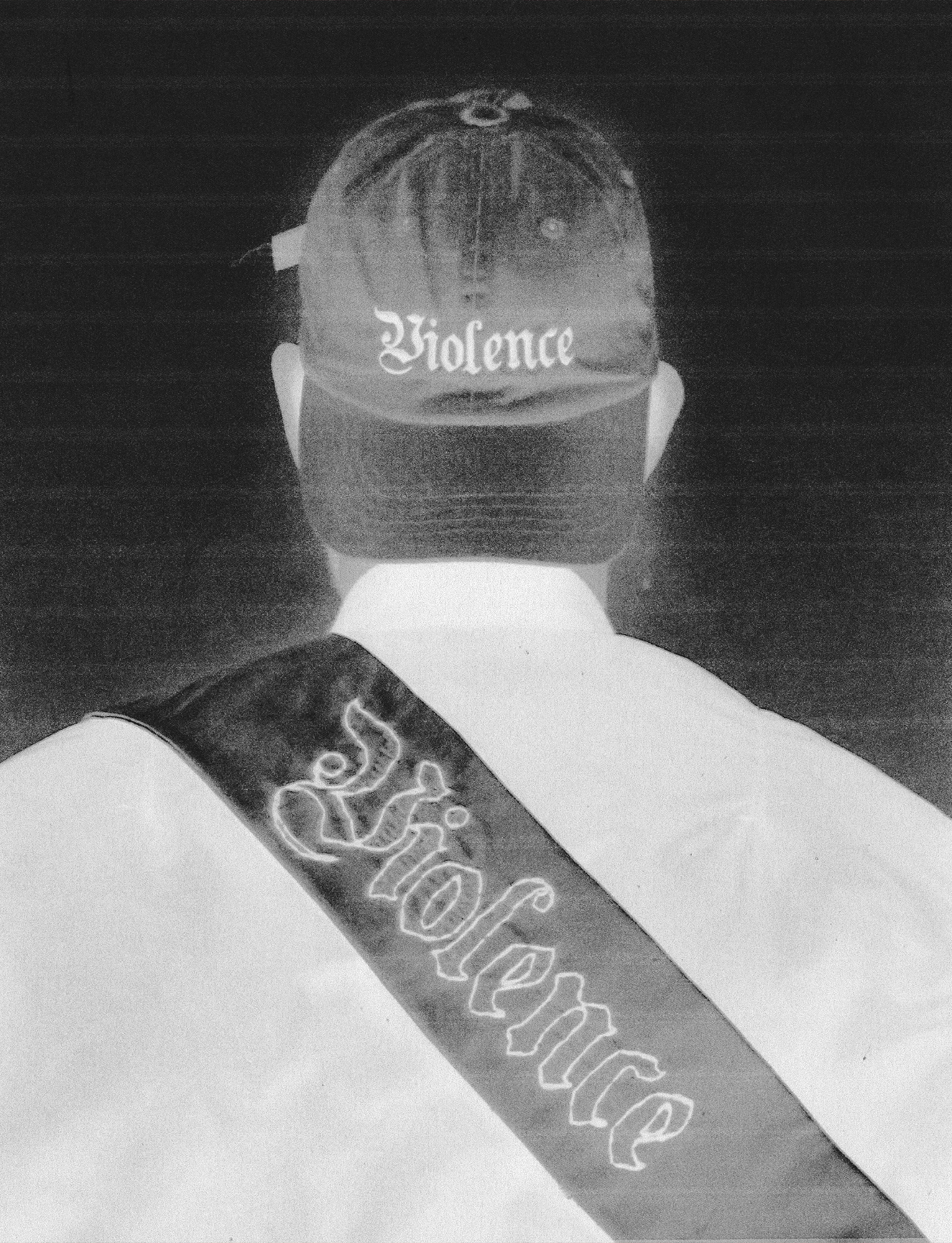

The words “violence” and “fun” can be synonymous

The Jackass boys’ suggestion that no chicks ought to be harmed in the making of their TV shows and movies seems far quainter after watching Paige Ginn’s videos than it did when Rad Girls aired — obviously, it is clear in 2021 that women should be doing whatever they feel like doing with their bodies, whether what they feel like doing is dieting or getting fat, having children or remaining staunchly childless, getting plastic surgery or getting fit or getting borderline concussed as a result of hurling themselves headlong into ten or fifteen storage boxes in a Walmart. There is something more punk, though — more possessed of a real, lusorious air of violence, and accordingly more dangerous and free — about Ginn’s stunts in particular than there was about the costumed, scripted MTV skits orchestrated by the Rad Girls. Here, one thinks, watching her videos on YouTube, is a woman who would probably agree with Hunter S. Thompson’s assertion, in the voicemail that he left for Johnny Knoxville, that the words “violence” and “fun” can be synonymous, the rush of being hurt but not being irreparably damaged something like the rush of drugs, or sex, or love. Nothing by the Rad Girls ever feels as pointless, and accordingly as giddy, as a compilation of Ginn’s “best falls” from 2013-2018, a five-year project with no aim, no purpose, no narrative and no obvious financial gain for its creator.

America loves a tomboy who still looks like a Victoria’s Secret model, an Olivia Munn or a circa-1967 Goldie Hawn, but there are limits — it is considered bad form to break or scar the merchandise. Vice magazine, a cultural touchstone Ginn might be a little too young to be familiar with, once ran a photograph in what it used to call its “Dos and Don’ts” of a beautiful young woman at a party, passed out after drinking one too many beers. “When women get all Weekend at Bernie’s,” the male caption-writer groaned, “it’s just not right. It’s like she fell asleep at the vagina, and that makes all mother’s sons feel uncomfortable.” The writer’s fear being for the woman’s hypothetical unborn son and not her safety, picturing her as the designated driver of her reproductive system and not as an actual person, is not terribly surprising when one considers the caption’s provenance: it will have been either edited or authored by the right-wing talking head Gavin McInnes, who progressed from being a co-founder of Vice to being the founder of the Proud Boys. Still, it perfectly encapsulates an irritatingly pervasive attitude towards the bodies of desirable young women, whose fertility and reproductive history are considered to be matters of general public interest. Ginn, to expand on the embarrassing, sexist Vice analogy, is not so much asleep behind her body’s wheel as she is steering it with the insane abandon of a seasoned rally driver, open-eyed and screaming, joyriding, crashing into barriers in order to experience the sick, effulgent pleasure of brushing up against death.

Just as adroit at upending sexual and social stereotypes is a mysterious one-minute clip added to YouTube in 2016, with the eloquently self-explanatory title British lads hit each other with chair. Four boys, aged somewhere between seventeen and twenty-three, are standing in the concrete backyard of a typical suburban home somewhere in Britain, quivering with the nervous energy of thoroughbreds before a race. One is shirtless, and another is in nothing but a pair of jogging shorts; both are fit, but in the manner of a labourer or a builder rather than a gym-rat, softened slightly by what one has to imagine is a steady flow of booze. The boy without a shirt goes first, having to swig wine from a bottle and then dash it, showily and dumbly, on the ground to build his courage; the boy wearing only shorts, moving with the eager fluidity of a Looney Tunes cartoon, lifts a folding garden chair above his head. What follows — the first boy being clobbered until he is on the ground, a third boy sweeping in to take a beating, the first boy returning determinedly to starting position and then being beaten until he is on the ground again — would be considered unremarkable in the pantheon of copycat Jackass stunts if it were not for the pervasive, intense air of homoeroticism colouring the entire chaotic stunt, in particular the video’s first seconds: before the ensuing violence, the two nearly-naked men lean in and, as if this were something they did frequently, exchange a soft, delicate kiss. It is a kiss as casual and honourable as a handshake, an assurance from the one man to the other that whatever may transpire, he will not come to irreparable harm — letting lips do what hands do, both participants appear to make a contract. Later in the video, when the first boy is on the ground after the second round of pain, the other keeps the promise made by that earlier kiss by cradling him, Pieta-like, the two men touching skin to skin. The willing victim seems to have experienced a transformative agony, his breathlessness and wide eyes closer to an erotic expression than a hurt one. “That’s ridiculous,” he repeats, twice, before another male voice somewhere off-screen offers an amazed-sounding corrective: “That’s fantastic.”

A body in immense pain can feel genderless

To read an intentional statement about gender roles into the porny, atheistic passion play of British lads hit each other with chair is more or less as ludicrous as doing so with one of Paige Ginn’s compilations of her various falls. Still, art can be an accident, and it is undeniable that both of these artefacts — especially paired — express a truth about the use of injury and agony as a conduit for escaping, or at least gratuitously fucking with, the gender binary. A body in immense pain can feel genderless, its status as a site of hurt more meaningful in the white-hot and blinding torrent of sensation brought on by a punch or kick or cut than its official designation as a body that is sexed. (It is worth noting, for example, that receiving a swift, killer kick directly to the testicles is a de facto male injury only if you believe — which I personally do not — that only men have testicles that can be kicked.)

Read More: Deep Sniff