What drew you to writing on food initially? And what was your entry to restaurant criticism?

I was always really passionate about food, and especially food TV. From quite a young age I was obsessed with cooking shows, people like Jamie Oliver and Nigella Lawson, and I was always interested in finding new places to go and eat. I was the one in my friendship group that, when we went on holiday to a new city, would kind of torment everyone with a guidebook: “We need to go to this restaurant that I’ve read about.” So there was a lot of that in the background.

In terms of work, I was a journalist covering all sorts of subjects, interviewing people from film, music, tech, and food was part of that. Then in 2018 I got to do a guest column for ES Magazine, they didn’t have a regular restaurant critic at the time so they were trying out various people. I loved it, and it felt like the culmination of all those years of obsession and passion about food, and food media. I had such a clear sense of how I wanted to approach it – the voice, the energy of the writing – and it went really well. I ended up getting the job as restaurant critic at ES, then three years ago I moved over to the paper, The Evening Standard.

One of the great things about restaurant writing; obviously food is the specific thing we’re talking about, but you get to interact with culture, you get to talk about cities and how they change, different neighbourhoods, how people socialise, you get to engage with how the world is changing. It’s this really universal, approachable way to dig into all sorts of other, bigger subjects.

Yes, food writing and restaurant criticism feels like a really interesting space currently, where food becomes a way to talk about identity, politics, class and much more, especially in major cities like London.

Over the last five years things like social media have been really important, and restaurant critics and food writers have been rightly held to account. Places like Vittles are doing amazing things, and Eater, which isn’t active in London anymore, but is still doing great stuff, it’s been a really positive shift. I think it’s only made the writing better, and I am always a real supporter and cheerleader for all different types of interesting, engaged food writing: more newsletters, more books, more food media, I just want to see more of it all.

Food is very universal

Legacy or traditional media can feel a little bit like a shrinking iceberg at times, because we’re losing a lot of columns, publications are closing. That’s a real shame, and while the landscape right now isn’t perfect, and there’s still a way to go, there have been positive strides in recent years. It would be great if they were emulated in other forms of criticism, but food is quite unique in that way, it’s very universal. Food writing feels like it’s underpinned by a lot of critical thought now, where people are asking questions about which restaurants and which cuisines get covered, whose taste is deemed to be the correct taste and things like that. It’s an exciting time.

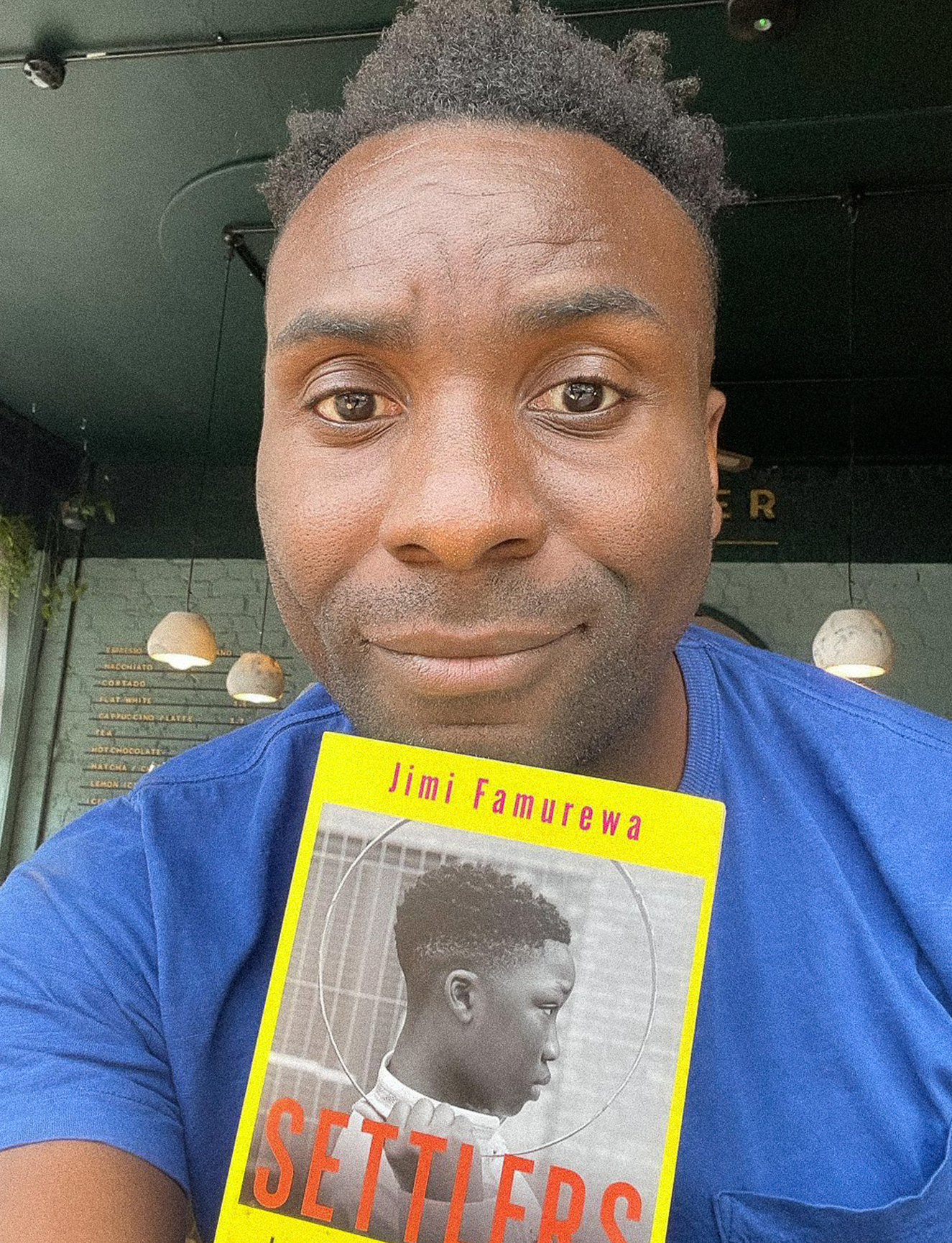

Your book Settlers manages to be both a wide-ranging study of Black African London, beginning with the 1960s arrivals from African countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe and Somalia, and, I’d argue, in part a memoir too. How did you arrive at the form for the book?

I started out thinking there’d be only a little bit of my story in the book. The idea initially came out of the fact that through my career as a journalist increasingly I was speaking to prominent Black people that I have a shared heritage with, people like Skepta and John Boyega, who are part of this broad legacy and generation. Although they came from different cultures in some instances there was a lot of shared history and shared traditions, and I was really intrigued by that. I had this sense that there was this really prominent, visible generation of Black Brits who belonged to a particular lineage and history, and that though there was overlap with the Windrush generation and the Caribbean community, that this was also a distinct tribe, and there wasn’t much in terms of specific historical investigation. I set out to connect the dots on various ‘pillars of life’, was how I thought of them.

These pillars ranged from food and restaurants, to family units through exploring the practice of West African children that were privately fostered with white families, to interactions with the police, to housing, religion, education. Initially I wanted to tell this story through other people’s quotes. I’m a journalist with probably two decades experience of interviewing people, telling a story through combining quotes with my own research and also fieldwork, and I wanted to apply that to this story; use other people to almost tell my own story.

Then, of course, in the practice of doing that you realise that you’ve got a degree of insight and your experience can hopefully illuminate things a little bit more. I realised, ‘I can tell you the statistics about Black interactions with the police or give you a little bit of history on the relations between Britons, Black Caribbean and Black African communities, but then I can bring it to life even more if I zoom in on my own experience.’ It probably became more of a memoir than I intended it to be, but I was always quite careful about what I was sharing; it was always about illuminating a certain point, or really driving something home.

I guess it’s a question of storytelling, and I suppose there’s also a freedom in the fact you have total authority over sharing your own stories.

I also wanted to challenge and test my own preconceptions. There were definitely examples where I started a chapter or followed a line of thinking with a really set idea of where it would lead, or what I wanted to discover, and then that would be changed by speaking to someone or finding some amazing piece of work that a social historian had done in the past. So it was a constant journey really.

But yes, fundamentally it’s storytelling. When I think about the book and what it was at its core, I wanted to tell people’s stories and be a conduit for that, and in doing that tell my own story as well, and find my place within this broader narrative that hopefully speaks specifically to those of similar Black African heritage, but also is about immigrant communities at large and how cities or countries change over time.

Did you have any apprehension in terms of writing about your community, and trying to do justice to them in the representation?

I really did, all the way through. Even now when I talk about things I’m always really conscious that I’m just one voice and one perspective. Hopefully it comes across in the book that I was very mindful of trying to wrap my arms around two things at once; be really honest and authentic to my own personal experience, but also recognise that there are really differing circumstances.

I’m just one voice

It’s always a danger when you get the opportunity to speak for marginalised or underrepresented communities, that you don’t convey the full experience. I even explore this in various parts throughout the book. For instance how we’ve seen in recent years that there’s been a real rise in the prominence of West African restaurants, but then within that, say they try an adaptive version of Jollof rice, then you have people saying, “That’s not Jollof rice, to me Jollof rice should be like…”

I’m interested in the role that food can have in preserving the identity of diasporic communities, while also acting as a bridge to the new place. I’m thinking of restaurants you mention in the book, like Ikoyi or Chishuru, which have been much-praised but are occasionally criticised for not being ‘authentic’ enough, can you speak a little on that?

In the book I wanted to capture the feeling of real world conversations and debate, and to have that liveliness to it. That was really interesting to me, the idea that West African cuisine, in particular, was presented as this untapped culinary terrain, and an exciting trend. There was a really fascinating tension, and I think this is often the case in diaspora communities, there’s such meaning and power in food, and you feel so possessive of these dishes and these tastes because they mean so much.

It’s been interesting to write about West African food over the last few years, in terms of it having almost a breakthrough moment, in some ways, in terms of prominence. There are other cuisines that are a bit further along in terms of, let’s say their reputation outside of the communities that they traditionally come from, like, say South Asian, East Asian or Chinese cuisine. It feels that in the UK it’s a recent thing that we’re able to recognise and respect different forms of West African cuisine, that it can be Michelin-level elevated, it can be kind of quite humble and hearty, it can be a bit fusion. We’re realising, slowly but surely, that there is no one true Jollof.

As a journalist yourself, how have you found being on the other side of a press cycle for Settlers?

It’s been strange to have poured so much into the book, and then instantly toggle into being a kind of ambassador for it, and trying to convince people that it’s worth their time. It’s quite surreal, I’m so used to being the person interviewing someone and asking the questions, but I think I am probably getting used to it now that I’m about ten months into the publicity trail.

What do you think makes a good restaurant critic?

To be a good restaurant critic you need to be quite tireless, in lots of ways. You need to be a bit of a natural optimist, because you’ve always got to be able to be excited about new restaurants, even as you get accustomed to the cycle of them, and you’re faced with quite a lot of the same things over and over again.

You need to be tireless

Also, being curious and being rigorous. This is something that I definitely try to emulate from the critics that I like; they really sweat the details, as well as being entertaining. To be able to memorably conjure the experience of eating something or being in a certain room, you do need a lot of rigour in terms of getting things right, doing the research.

So for all that it looks like the cushiest gig in the world, it is a lot of work to continue to be good at it, I think that aspect of it is kind of underrated. But obviously, the rewards of the job are self-evident, it’s such an amazing privilege to get to do it.

Read More: Gut Level: A Space For Freaks