Walk down the street in Shoreditch on any given day and you’ll see them plastered over every available surface. Even on tiny Caribbean islands, you’ll find dancehall enthusiasts making their passions clear via their car bumper.

Versatility has been key to the sticker’s long life, and its constant reinvention stands to proves there is little it can’t do — or be. Not only that, but stickers are incredibly accessible; almost anyone can use them as a canvas. As such an adaptable and readily available medium, it makes sense that artists have adopted stickers as a means to share their work with the world.

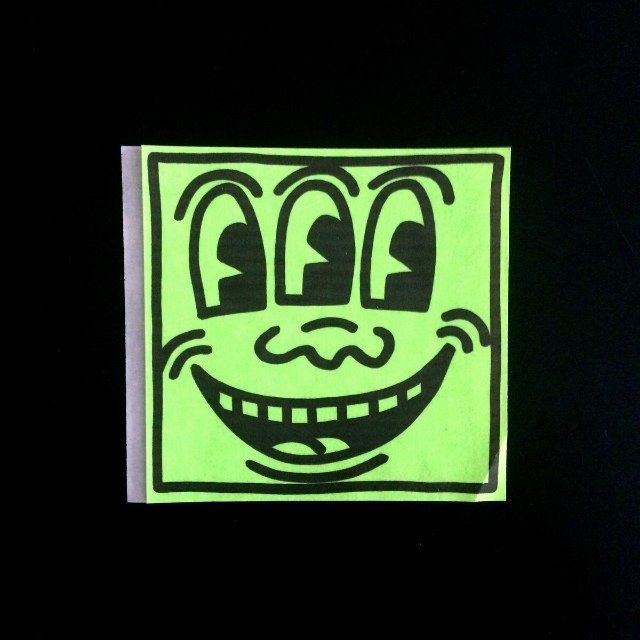

For the late artist Keith Haring, stickers were a solution to his moral dilemmas of working in the art world. Having spent his career working publicly (and illegally) across sidewalks and subways, Haring found himself in a predicament when he rose to prominence in the mid-‘80s.

In high demand in the New York gallery scene, and with requests flooding in from high-profile institutions and individuals, Haring sought a way to keep his connection to the streets, believing art should be for everyone. From this pressure emerged an incredible and revolutionary way of producing artwork. Haring took already popular forms of merchandise — key rings, T-shirts and, of course, stickers — and turned them into art, founding Pop Shop in 1986.

It’s clear that the humble sticker is already moving with the times

The conceptual space took the city by storm and had people from all over queueing for the chance to own Haring’s artwork. Yet despite this positivity, the art world remained sceptical; many saw it as disrespect for art and a cheapening of it. But Haring’s ‘selling out’ was in many ways an incredible comment on elitism in the industry. John Gruen, in his biography of Haring, described Pop Shop as a place where, “not only collectors could come, but also kids from the Bronx”.

By offering cheap alternatives to his expensive works, Haring ensured that his art was accessible. Those with a lot of money bought the canvases, those with a little bought the T-shirts, and those with less still bought the stickers: Haring managed to bridge the gap in the art world by functioning across all levels.

Haring’s values are echoed in the work of many artists operating today, particularly within street art. Unwilling to compromise in making work for everyone, many bypass institutions and take their art outside for all to see. But with this methodology comes inevitable risks. For a long time, many street artists have used stickers as their medium of choice when producing work, and for good reason.

Not only does the speed of application massively decrease the danger of being caught putting up art, but the abundance in which stickers can be produced (and for minimal cost) means that one design can be put up in hundreds of places around a city. Street artist Shepard Fairey used this way of working to great effect when putting out his OBEY campaign. He put his art up around New York City at such a rate, that soon everyone was questioning the meaning behind the suddenly ubiquitous black and white face of Andre the Giant.

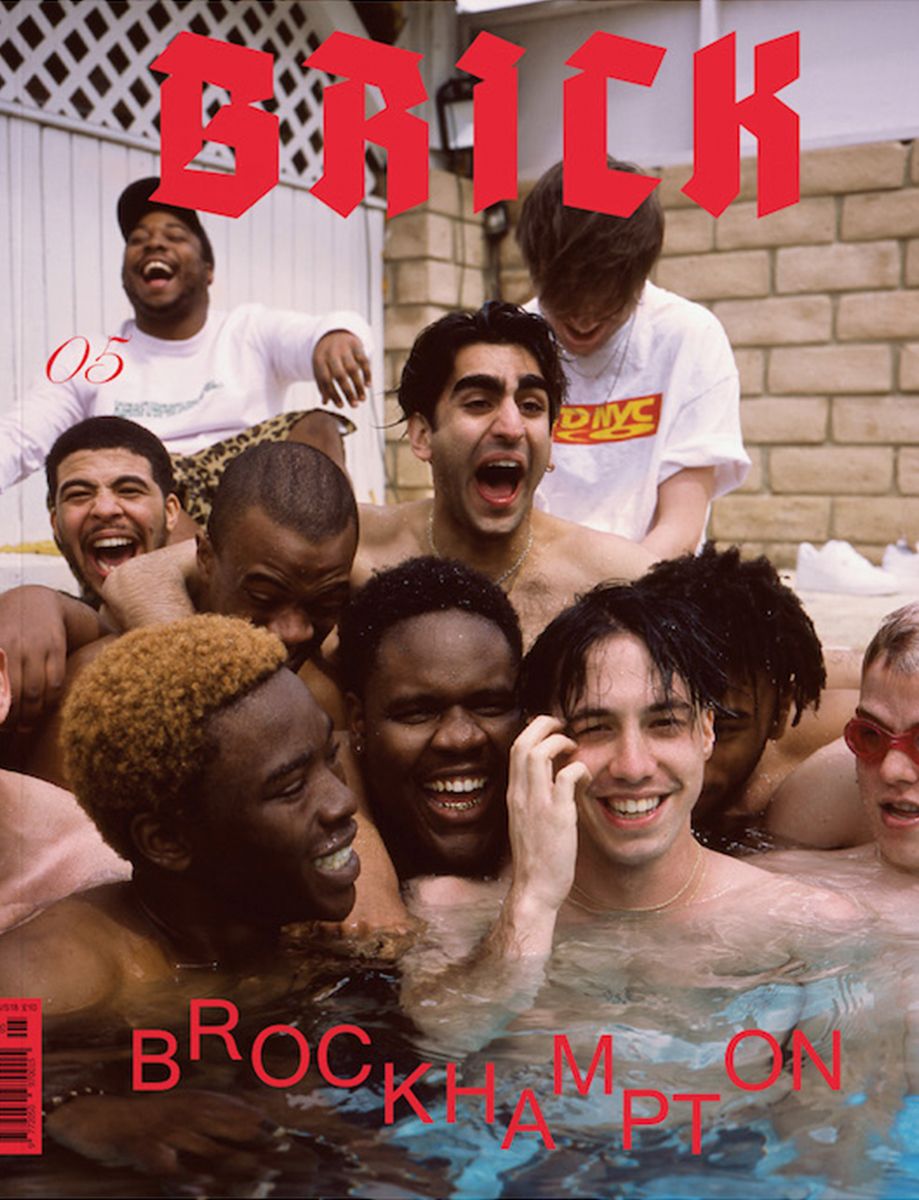

With close links to street art, the skate scene has been pioneering insane sticker designs for years. More and more, you see brands collaborating with huge artists on collections, creating a space where high art meets street culture. In doing so, the work of the artist becomes accessible on a whole new platform and to a brand new audience.

Supreme’s collaboration with Damien Hirst in 2009 saw them produce not only skate decks and T-shirts bearing the artwork but a whole load of stickers. Given some of Hirst’s works sell for millions at auction, it’s incredible that teenagers can now own their own for a fiver instead.

Obviously, a sticker and an original artwork are incomparable in many ways, but what the sticker embodies is the chance for a new audience to not only experience the art but have a version of it for themselves. No longer is art restricted to the gilded frames of West London townhouses, now it can be found on the underside of a scratched up skateboard in Brixton.

It’s clear that the humble sticker is already moving with the times. There have even been efforts to branch out towards a more sustainable future through material innovations which go way beyond the classic vinyl adhesive. From the way things are looking, soon we’ll all be able to expand our art collection to Koons and Kahlos — with the odd shiny thrown in. It’s probably about time to dig out that old shoebox again.

Continue the nostalgia trip and read about the complex history of the hoodie here.