I doubt any of us will see a Kardashian in a 9am Zoom stand-up, or get a connection request on The Dots from a Love Island contestant. But the trend highlights the opacity of creative industry titles and structures. That’s creative and artistic directors, but also curators, in-house stylists and designers. These titles can be as opaque and loosely defined as they are good at holding allure and transient social value. Further, creative industry structures have long been multifarious – propped up by invisible networks, nepotism, and long term unpaid internships – and on the other end of the spectrum, the labour on the lower-rungs is all-encompassing (eloquently meme-ified by the likes of @FashionAssistants).

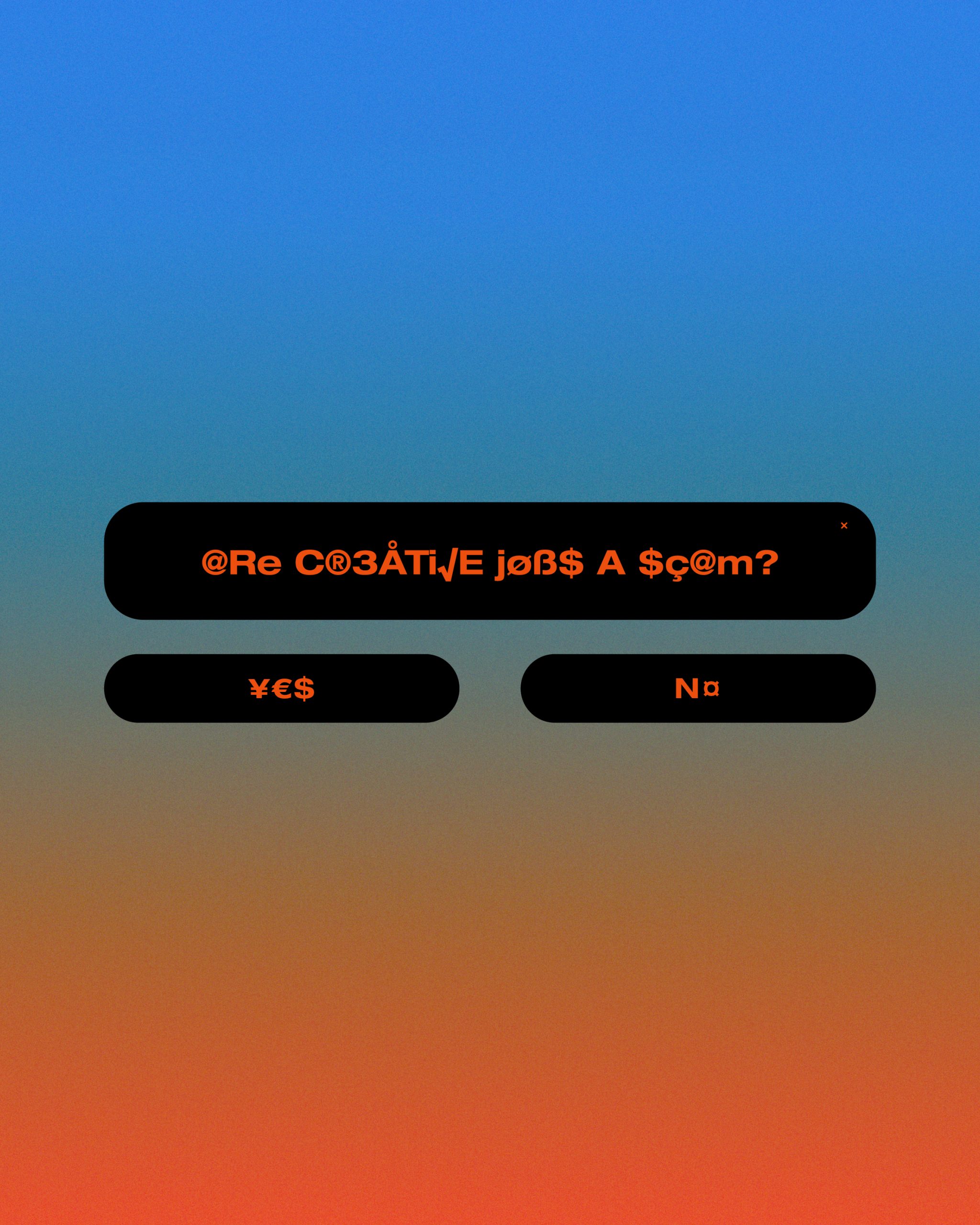

Does this tough-to-crack industry fuel misconceptions for people pursuing creative work, and what they believe will bring creative freedom, social capital, and opportunities? We don’t need to worry about a Hadid or a Jenner stealing our jobs, but how ‘creative’ is the creative industry for the majority?

Sociologist Dr. Nan Lin projected an evolution in our values and priorities around work two decades ago, in their seminal 1999 paper, “Building A Network Theory Of Social Capital”: “We are witnessing a revolutionary rise of social capital, as represented by cyber-networks. In fact, we are witnessing a new era where social capital will soon supersede personal capital in significance and effect.”

The social capital from creative jobs can be the trade-off for terrible working conditions, but it’s often acquired with economic support – ‘the bank of mum and dad’ – as well as obscured and informal networks. Ringfenced positions have an undeniable prestige, whether the job is truly ‘creative’ or not. Is the chief creative officer in luxury fashion doing much of the actual creating? Either way, they are the individuals championed as expounding the vision, from which they benefit – all while “exposure” is still a currency schilled to young creatives.

Freya Jewitt from Arts Emergency says: “Creative workers are often passionate about the arts, believe in its power for good, and find work a key part of their identity. This can be exploited in the cultural sector, where people are expected to accept precarious working conditions or working for free, as part and parcel of ‘doing what you love’.”

The ladder to these upper echelons leaves young people locked out of opportunities and creative freedom, and locked into a rat race. Research has shown that the pressure to find a ‘calling’ leaves young people anxious and depressed. The numbers speak to the industry’s impenetrability: a study by Arts Emergency says that just 16% of people in the creative industries are from a working-class background. Only 9% of those in film, radio, and TV are Black, Asian, or from a minority ethnic background, while it’s 4.8% in music, visual, and performing arts.

Personal networks and insider knowledge remain vital to getting in

Jewitt says: “The exclusivity of these industries rarely changes because, in order to maintain their monopoly on the social capital that comes with a ‘cultural’ job, the people at the top maintain steadfastly that the arts are a genuine meritocracy. In reality, personal networks and insider knowledge remain vital to getting in. A reliance on precarious and relatively invisible freelancers also intensifies inequalities, locking many talented people out of the sector and leadership roles.”

“I’ve often been told, or it’s been alluded to, that my job as ‘a creative’ is a luxury – because I love what I do,” says Ashleigh Kane, a creative consultant, writer, and former Dazed art and photography editor. “People would say, ‘There’s someone else ready to take your place if you don’t want it’. It felt like the sacrifices I had to make in order to do that were a part of that life. Almost 10 years into my career, and a year into being freelance, I realise that’s absolutely not the case.”

The Creative Industries Federation says 47% of creative workers are self-employed, compared with 15% across the workforce as a whole. Indeed, we’ve seen the rise of the ‘content creator’ in tandem with the freelance economy, as young people attempt to break away from the sector’s outdated structures – essentially, a catch-all for a photographer, videographer, editor, sound recorder, illustrator, designer, web designer, creative lead.

Russell Dean Stone is a creative director, editor, consultant, and writer, who teaches on the Middlesex University Fashion Communication course. He highlights how many editorial publications rely on creative work, but that it’s not reflected in pay. “They are often the kind of all-consuming jobs where it’s hard to have boundaries with working hours,” Stone says. “I don’t think getting to do creative work means you shouldn’t have a great working environment.”

“That is the sad reality of some creative jobs. People do them to get experience, and do work that allows them to springboard quickly to other opportunities that pay better – who can blame them! We’re still in this model of trading creativity for opportunities for portfolio.”

We’re still in this model of trading creativity for opportunities for portfolio

The creative industries and brands have a symbiotic relationship – brands crave the cultural relevance of creatives (say, a fashion magazine), while creatives require the brand money (for example commercial editorial that sits alongside the organic). But in Stone’s experience, the cash is not adequately invested back into creative budgets to maximise profits either.

“Publications use talented and well-meaning editorial teams as a front for them doing this,” he says. “It is great to see independent platforms like gal-dem striving to work in different ways, to create opportunities and compensate people fairly. I implore brands to be more conscious about who they spend budgets with and support.”

“Companies definitely use it to their advantage and it is exploitation,” Kane continues. “It’s just wrapped up in a cool package with the promise of parties, events. Especially in London. I think there’s a balance – that validation and social capital have helped me, but ultimately, creatives should be paid the same as ‘less alluring’ industries.”

So when crafting your own creative career, how do young photographers, directors, or balance the work that pays the bills and their true passion projects – is there a sweet spot?

Keeping an open stream of editorial work or personal projects can help you retain creative autonomy

Client-focused creative work, whether it’s a music video or working with a brand, is ultimately going to be about compromise and fulfilling a client brief, says Stone. “Keeping an open stream of editorial work or personal projects can help you retain creative autonomy. It’s nothing new for creatives to juggle creative, personal, and editorial work against commercial work. They often feed off of each other in positive ways – editorial work gets you the ‘money work’.”

He adds: “Creativity and commerce go hand-in-hand, and I approach any project with the same intention: to make the most magic possible within the constraints of timing, budget. I am someone that throws themselves all in on projects, and I am still learning what that balance looks like for me.”

“I am fortunate enough that there’s always some enjoyment in the work I get to do, but it’s true there is a lot less time to focus on passion projects – things that I get satisfaction from that aren’t monetary,” says Kane. “I am not working on anything that isn’t for a client. It’s important that I’m really gunning to establish myself and get some savings underneath me so I can set myself up for a future.”

How do we resist our future cultural landscape being populated exclusively by the children of the wealthy and well-connected, with lofty titles? How do we take control of the gig economy and push pack against the precarity of freelance life?

The Dazed Academy sessions, an educational initiative for aspiring creatives who seek a different route into the industry, ran a workshop specifically on the less outward-facing creative roles in making a magazine, from design to sales and production. Last year, fashion saw the launch of the Rubric Initiative, which is “working with leading industry figures to create educational resources and mentorship programmes, arranging outreach initiatives and paid internship placements, and by promoting transparent dialogues about race, class and gender in the creative fields”. Jewitt highlights the importance of structural industry change with mentoring, like Arts Emergency’s scheme, to tear down gatekeeping and encourage underrepresented young people to chart their own course into the industry with informed choices.

Whatever level you’re at, you can help make the sector more equitable and transparent

“While we’re deeply committed to getting young people into the industry, we know that it can be hard to navigate once you’re in, especially for perceived ‘outsiders’. Organisations still have much more to do to tackle toxic workplace cultures,” Jewitt says. Arts Emergency runs workshops on topics including imposter syndrome, rights at work, and microaggressions.

Whatever level you’re at, you can help make the sector more equitable and transparent. Jewitt calls on recruiters to rethink their processes: “Next time you are hiring, recruit better: offer guidance ahead of job interviews, show the salary, give alternative ways to apply, make non-grads welcome, and share feedback. It’s crucial that those with the power to do so pay a living wage, support flexible working and good parental leave and pay.” While we can’t rely on Cardi or a Hadid sister to demystify the creative industry’s top tiers, it’s clear that there’s some top-down responsibility that needs to be taken to make the creative industries truly ‘creative’ for everyone.

Read More: How To Handle Creative Compromise