For years, we’ve been trying to define queer. We’ve given it all kinds of synonyms, but it always seems to evade being nailed down. Which is, arguably, the point. And over time you come to realise that perhaps it can’t be named because queerness isn’t simply a word, nor a definition, but an act, a practice. Kind of how bell hooks described love.

For years, we’ve been trying to define queer

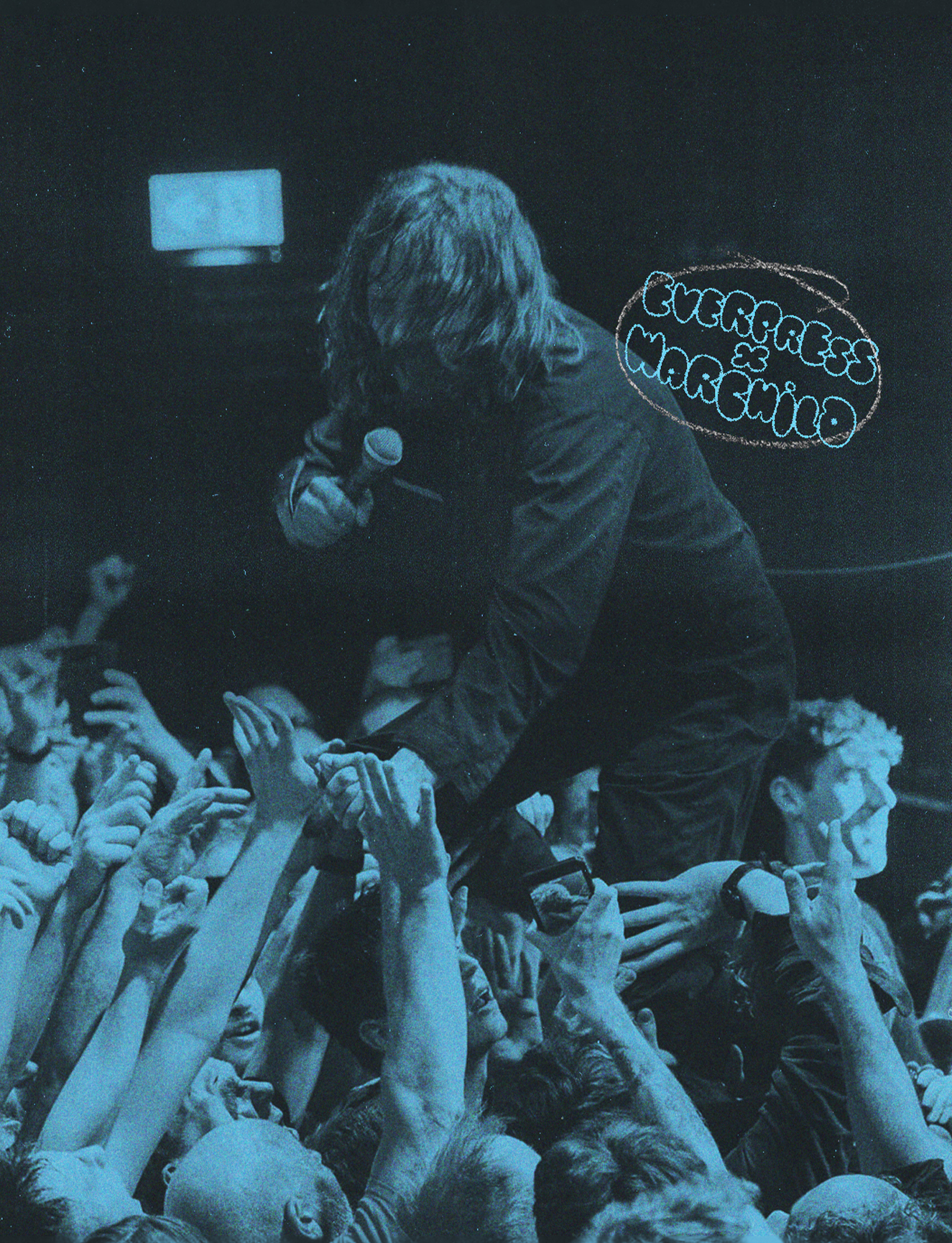

And queerness is an act. A practice of reaching up high, grabbing at something almost in your grasp. Queerness is an act, a practice that is a quest; an act, to quote José Esteban Muñoz that seeks the horizon and never the shore. A practice of communion. A practice of self-recognition and self-healing. An act of learning how to be on the outside, and thriving on that, cherishing that.

And so it’s these practices that makes clubbing feel inherent to queerness, and queerness feel inherent to clubbing. This isn’t to say that in order to be queer you have to be into hardcore gabber and shelving pills, or even going clubbing at all, but there is something about stomping your feet on a dance floor that feels like all of those practices above in action, not in thought. And god knows we need action. We’ve been to clubs across the world, and made friends in smoking areas, on dance floors, and in dark rooms alike: friends with whom, for a night, you are on this quest. A quest for euphoria, for utopia. A quest to find, express, your queerness.

Queerness is an act that seeks the horizon, never the shore

In her essay, “A Tribute to Shy Girls on the Dancefloor”, Brittany Newell talks about how clubbing, dancing with a massive group of people, can be a way to deal with social anxiety. “It’s a way of being with people without needing to talk […] more than making out or freaking out, I look forward to zoning out on a dancefloor, where the bodies are hard but the collective gaze soft. The creeper urge to stare is made neutral, shyness alchemized into a chill way of being near others. I like the proximity without commitment.”

Here is where clubbing starts. Of course the queer clubber is not always shy, but in the queer space the clubber is always working something out, healing something, trying something new. This ability clubbing, dancing, gives us to zone out, to be neutralised when we are often such politicised bodies, to be in close proximity to others without committing to more than that, is why clubbing still feels like one of queerness’s revolutionary internal organs.

Clubbing is about countless conflicting practices

And clubbing, for queers, is about countless conflicting practices: it reminds us of the importance conflict has in learning about ourselves. It is about experimentation and the expression of individuality. But unlike that moment on the U-Bahn where everyone is staring, this clubbing, queer clubbing, is about the ability to look and feel how you want, while being able to disappear; to dissolve into the collective consciousness that Newell writes about. There’s few other places in the world where you can be truly alone and totally together: the music making it impossible to have to talk, or perform, and so in the queer club you are invited to feel, to emote. This idea for someone, say, dressed in drag — is a radical one. To be so visible, and to be able to disappear. Queer clubbing gives us options, in a world where we are told what to do.

Historically, we would meet in Molly Houses with black-washed windows. We would know where to go—and when the spaces inevitably closed down because either the police raided them or the greedy heterosexuals decided they were cool—we knew where to go next. And in these places we would find ourselves, our community, our reflection, and our desire. We would catch eyes, bite lips, dance sweaty, and close with bodies which can barely touch outside the club for fear of violence. It’s amiss to assume that this queer clubbing isn’t about sex and sexuality too. Here, in many cases, we go to fuck. We go to fuck in our public, we go to be seen fucking, or kissing, or dancing sexually. We go to express our affection because it is policed everywhere else. Just like our bodies, just like our friendships. And this is a huge part of clubbing — the ability to express emotion and commitment to your friends too. To be gay, faggots, dykes, without having to wear the cloak you wear all the time when the club is over for another week.

Queer clubbing gives us options

It’s naive to boil the entirety of queerness and queer identity down to the act of clubbing — in fact, this idea is often used to flatten our real life experiences into one of mere promiscuity and hedonism. It’s also naive to assume every queer club is a utopia. As with anything which is a microcosm of society — the club can so often contain its class hierarchies, its race hierarchies, its body hierarchies, its gender hierarchies. And so—just as it should be—we engage in the practice of striving for better, of reaching up. Of going on a quest to find the best way to bring the most of us to euphoria, and utopia. Often we’ll fail — but sometimes we will succeed. And when we do…

Read More: INFERNO: The Nicest Party In London