What prompted you to start INFERNO?

Lewis Burton: It was really born out of lots of different frustrations. The major one was with London’s queer scene, which at the time was very white, very gay, very masculine, very male-centric, and every club was playing house music and disco, which was fun for a certain period, but after three or four years of hearing the same thing in every single queer venue and club night in East London, I just got really fed up. Me and my friends were complaining about it for so long, and then I just said, “Why are we complaining about it? I’m going to do it, I’m going to make it happen.” I really love the quote, “Be the change that you want to see.” Cool, I’m going to do it, I’m going to do this for everyone, I’m going to make the space that’s needed.

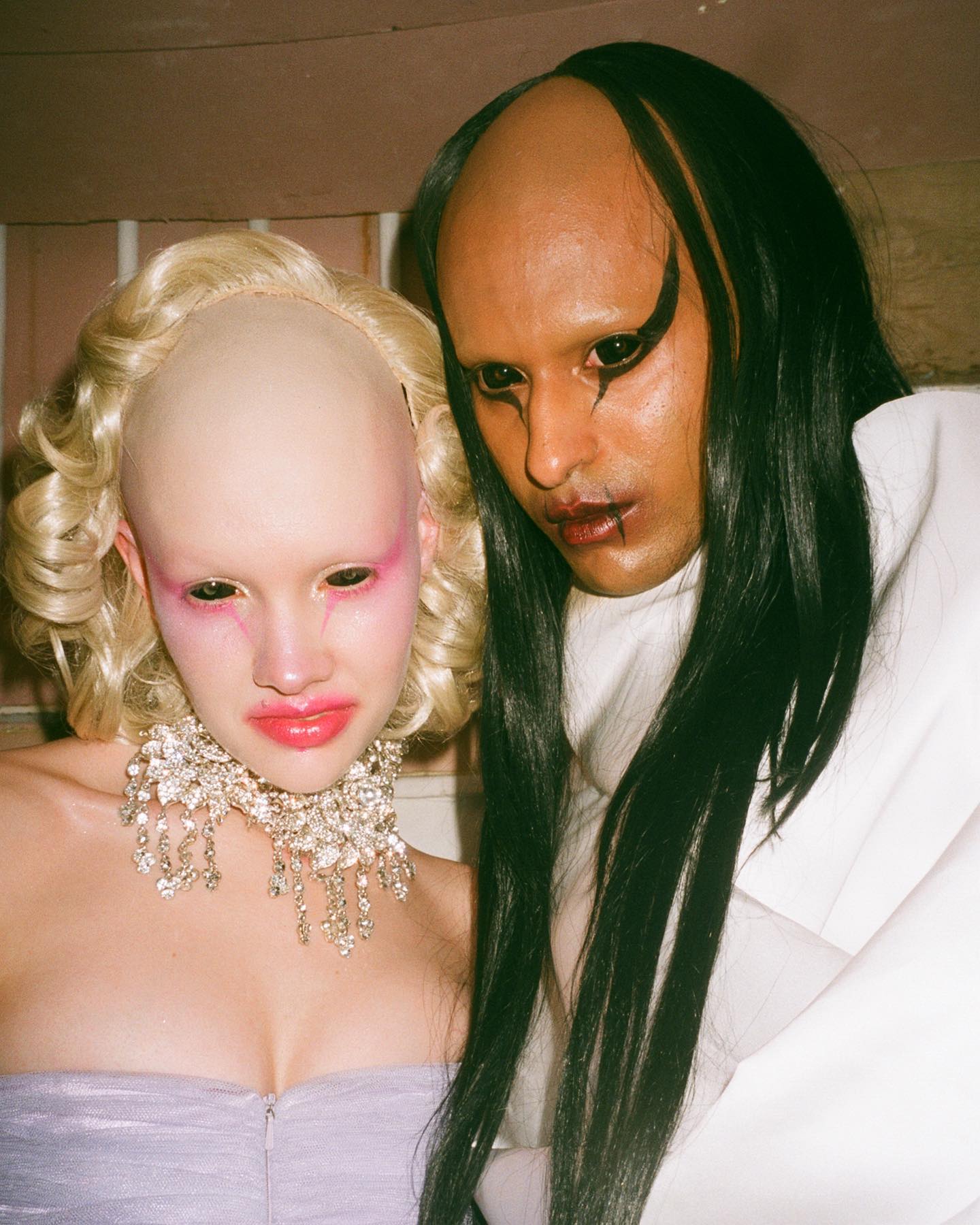

I’d just left art school at the time as well, so I was really frustrated that I was trying to sustain myself, do my own practice, and that was impossible as a working class queer artist just coming out of art school. I felt like the institutions and the art world snubbed me a bit, and some of my peers too, for making work that was too radically queer, or that was about queerness. And then our work was too transgressive for cabaret or drag spaces too.

INFERNO was really about creating a space for my community

So INFERNO was really about creating a space for my community, my friends, my peers who are artists, and who were making really amazing work at the time, and doing something completely different to what everyone else was doing. I love techno, lots of my friends did, but we weren’t really hearing it out, if you wanted to go to hear techno you had to go to a straight club night.

The discourse around queer identity especially has changed so much over the last seven years. In a way you started outside the mainstream and now the mainstream has shifted and come to you. How has that been?

LB: It’s been quite, I was going to say validating but it’s not validating, that’s not the word that I’d use. On the night of Brexit in January 2020 we got to do a takeover of the ICA in London, so we got to be actually in the gallery, doing a rave from 10pm until 6am. It was such a special moment for me because I did start INFERNO as a rebellion against these institutions snubbing me and my friends, so for them now to be welcoming us and paying us and celebrating us and platforming us, it was really special for the community around INFERNO.

It was just good to be recognised for that, that these things I’ve been doing in nightlife spaces didn’t go unrecognised. Sometimes things can be quite insular, but I put so much love into my community. I offer mentorships for younger, queer artists who are in a similar position to where I was seven years ago. I’ve got performers who still perform and make work for INFERNO, who’ve been doing it since the first few parties.

Our resident visual artist, sweatmother, they do a lot of work within institutions and galleries, but the work that gets picked is never their radical queer work. With it being our anniversary we’ve been talking a lot about everything going on, and they just had a moment with me a few weeks ago where they said, “Thank you for giving me space, and paying me, to make work that nobody else would, and believing in that, and believing in my queerness, and celebrating that.” I just said, “That’s what we’re here for, it’s what we do.”

That speaks to part of the importance of clubs and nightlife spaces, doesn’t it, they can be both spaces for community, but also facilitate culture that doesn’t sit within traditional culture spaces.

LB: 100%. I have been having lots of dialogues between myself and the INFERNO team, but also with a lot of other promoters and collectives around London, who use nightlife as a space to meet community, to find community, to support community. It’s also a space for culture and art and music to thrive in. Berlin now, Berghain for example, has been given cultural significance. I really feel like the UK needs to take a stance like that as well, and really celebrate the nightclub, and especially queer nightlife. These are institutions of culture, they’re a breeding ground for so much talent. Think of all the amazing people nightlife has helped create!

Clubs are institutions of culture

I think it’s really hard to find a scene, or create a scene, if you don’t have physical spaces. There’s things that social media and the internet just can’t do.

LB: It didn’t happen in the pandemic. We tried to make it happen, but it was just not the same. There were times at the beginning where we did some streams, and it was really great to help people when there was so much uncertainty, but I think with the longevity of the lockdowns, people got bored quite fast.

What’s your relationship like other London queer collectives who are pushing nightlife forward?

LB: I used to be part of Pxssy Palace, so I’ve got a really good relationship with Nadine Noor Ahmed and the rest of the team over there. We often meet up and have a catch up just as friends, but we all obviously talk about nightlife stuff because we’re just so ingrained with it, because it’s just who we are as people.

And through the years mentoring people and INFERNO, I’ve got a really good relationship with lots of the younger generation, and I’m often a soundboard for them when they come to me with their ideas, people like Lucia Blayke, who runs Harpies, loads of the other kids who’ve done new club nights that they’re trying out.

The word ‘community’ gets used a lot, maybe to the extent now that it’s kind of lost its meaning. But I think that’s a really nice vision of how community should look; you’re all in this space, doing similar things, but it’s supportive.

LB: No definitely. When I first started in nightlife it was very competitive. It was run by all the white cis masc gays, and it was almost teetering a bit on bullying, it very much made me think, you throw this word community around so much, but you do not understand what community is. And I feel like I’ve been very authentic to stay true to that, and help support, and actually nurture, and listen and soundboard, and I’ve often got that from my friends and peers in return, and the rest of my community, we do look out for each other. The scene right now is a much more loving, supportive, kinder place.

Do you think you’ve helped define the scene, or has it shaped INFERNO, or both?

LB: I mean, I hope to have helped the scene. I’ve definitely put in the work and the love and support, and I’ve definitely got it back too from the community. But just because of who I am as a person it’s just me being me, and being quite maternal, and looking after people. A bit of a mother hen.

When it comes to carving out a club space of your own, what’s more important; exclusivity or inclusivity? And is there a way of achieving a balance between the two?

LB: It’s been hard, there have been so many iterations of INFERNO over the years. When we started at Dalston Superstore, they really did take a chance on us to do something different there, and then after about two years we left, and started to do quite a few squat parties. The squatting community is quite white, very working class, very manly and straight, and eventually we decided it wasn’t quite right for our community, so we went back to doing venues. Also the stress of doing illegal parties was A Lot.

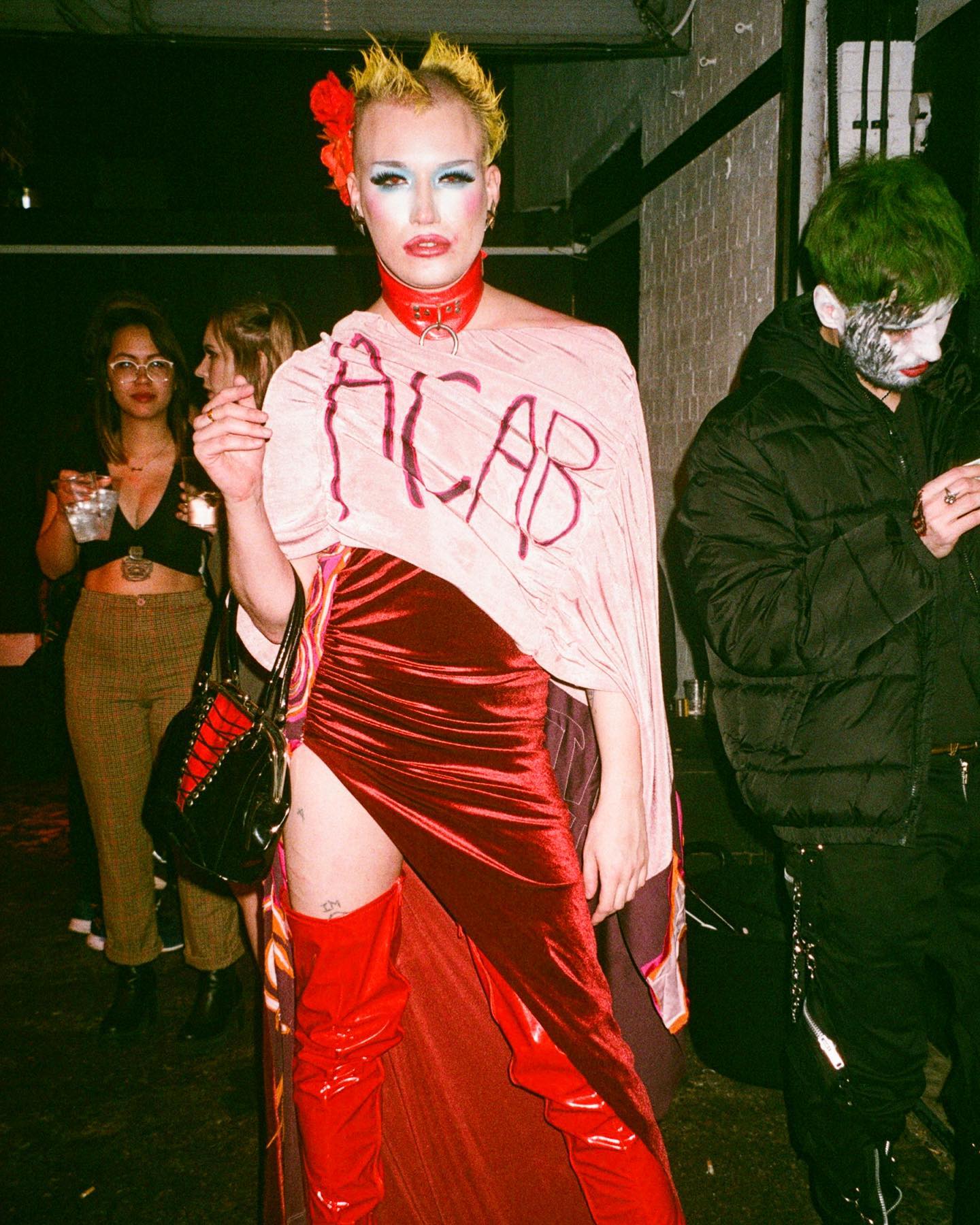

It was very organic in the beginning, just me and a couple of my friends and their close friends, maybe 150 of us in total. As time has gone on and we’ve had more conversations around creating safe spaces, I guess I was always doing that, but without the language that we had. I’ve tried not to discriminate against anybody, but doing those squat parties really opened my eyes to the fact that maybe we should limit the amount of, especially straight white cis het men, in these spaces, because, one: they can make queer people, women and femmes, feel very uncomfortable, and two: they’re taking up space when a queer person could be there.

We want to offer a space where people can explore their queerness

Especially considering we’re selling out every party now, for me, it’s about the fact that they can go anywhere they want in the world without prejudice. We have one night a month in INFERNO, where you can come, dress up, express yourself, be your most authentic version of yourself, express your gender identity, your true identity. I think if we did open up the space to everybody it would really stop, people would stop dressing up as much, and stop exploring their gender. But also at the same time, we do let some straight white cis het men in, because I think it’s really important for people to be able to come and explore their own sexuality and gender expression. We do want to offer a space where people can explore their queerness at any age, and find their queerness at any age, and maybe being in a party like INFERNO could be the catalyst for that happening, providing a safe space for that.

What have been some of your favourite, and maybe also some of your defining moments over the years?

LB: There’s been so many. Even the squat parties, as much as they were chaotic and a lot of hard work, they were also fucking fabulous. I remember one we did in this huge basement squat, where we were collaborating with Chronic Illness; the basement flooded the night before, so the day of the party we were all down there with buckets, creating this chain to scoop up the water, and the DJ was on a raised platform so none of their equipment would get damaged. It was a nightmare but it was also fab.

We got to do an iteration of INFERNO in my favourite venue, the place I grew up in in London, East Bloc. It’s no longer here but it was my favourite club night, ran by Larry Tee, who produced loads of Ru Paul’s music. Getting to do INFERNO in the club that had helped me come into myself, it was one of the best nights of my life.

The years at The Yard, we had the best time at The Yard, so much so that I should probably have left a year sooner, but I didn’t, because I just loved being there, the community loved being there. It was the first time we’d really been recognised for the hard work we were doing for the queer community, and trying to change things within the arts, and platforming queer and trans and femme DJs as well. Nearly every party at The Yard was spectacular, it was a really special moment for us.

Why should you have left a year earlier than you did, at The Yard?

LB: Because there were queues of people outside, waiting to get in, and we had to turn even queer people away, who were in looks, because we were at capacity. Hundreds of people would be outside waiting, and I just felt so awful. We needed to bite the bullet and go to a bigger space, so we went to Mick’s Garage, which is now Colour Factory, and we did one party there before the pandemic, literally six days before that first lockdown. Now at Colour Factory, being in that space and having over a thousand queers there now, it’s just madness, we can’t quite believe it.

You started as a very intimate, word of mouth, night. How do you preserve that character when it gets to be as big as 1000 people?

LB: I think INFERNO has stayed true to our ethics and our morals and our sense of community, because we still have people who’ve been there since day one, who are still there now and come to every party, so they kind of teach and educate and take the kids under their wing. One of my favourite things is when people say it’s the nicest party in London – everybody is so respectful of each other, and asks pronouns. I feel like people get that sense from dressing up, they get a bit more confidence for the night as well, where they’re willing to put themselves out there and just feel content in a safe space to be able to do that.

We still have people who’ve been there since day one

Lots of people have found their community, their friendship circles, through going to INFERNO, and I think that’s helped the night stay kind and humble. But also I think it’s about who we are, the team that runs it, we’ve actively made sure that we check in with the community, and do our bit as well to keep that going. We’ve always had the support, and we’ve never had to worry about it, or market the night or whatever, it’s been very authentic and very organic. It’s just happened. I’m so grateful for it.

London nightlife, for years, has been under threat. How do you feel the pandemic has affected nightlife? And relatedly, though we’ve touched on this a little, how important do you think clubs are to cities?

L: I mean the true pandemic is nightlife closure and the clearing of nightlife and club spaces to make way for fucking luxury flats. It’s ridiculous. We are getting further and further pushed out of the city centre, the people who have made these places so vibrant and beautiful, and brought culture and creativity and artistry to them.

It’s so frustrating. Colour Factory is getting knocked down at the end of this year to make luxury flats in Hackney Wick, and the only space that will be saying in that part of town is The Yard theatre, because it’s a theatre space, and it’s been granted a cultural significance, but actually all clubs provide that as well.

At this point I actually don’t know where I’m going to take INFERNO when Colour Factory goes, because we don’t have any medium-sized spaces left. There are no specific queer spaces that hold 500-1000 people, so I’m thinking, ‘Where am I going to take INFERNO? Scale back?” I can’t really take a step back because the community is there now, I’d be turning people away again and that’s not fair, right? So where do we go moving forward? It’s something we’re navigating now and it’s a real thing, and we need more support from the government, we need more spaces, we need nightlife to be recognised as cultural institutions, and breeding grounds of creativity and world class art.

What does the future look like for INFERNO?

LB: Right now we need to find a venue, that’s the future of INFERNO. We have a really exciting year programmed and planned at Colour Factory until it closes, but we’re just going to play it by ear and see where the winds take us.

With the nightclub crisis at the moment I’m thinking, “I could look into opening my own venue, I could make it happen…” But I’m also in this moment where I just want to make art and be creative, first and foremost, because that’s when I’m happiest. If I open a venue I’m going to spend the next three years bloody well doing that, it’s going to take up a lot of my time. I’m very much that person who loves the challenge of doing something new, get in and smash it, but it will take years out of my life. I’ve been doing this for 10 years now, and there’s a lot of rich queers on the scene; “Babe you could be buying us a venue! I see you with your one bedroom flat in central London!”

Read More: Diary Of Ending A Drag Queen: Why I Killed My Alter Ego