The latter has been the focus of Just Stop Oil. Members of the group have hit the headlines after zip tying themselves to football goalposts, glueing themselves to classic paintings, and forcing the closure of motorways, their orange Hi Vis vests an instant, but nuanced, identifier for the meaning behind the action. Typically worn by construction workers or road maintenance teams, the ubiquitous vests, one member told me, offer a sense of identity of being on the road. It’s a familiar uniform, flipped on its head contextually, and an echo of the yellow Hi Vis of the ‘gilet jaune’ movement in France.

It’s a familiar uniform, flipped on its head contextually

Hi Vis-wearing groups might be relatively new on the scene, but using clothes as a means of protest is not. “For as long as people have adorned their bodies, there has been a political or protest element to it at various times across cultures. If you don’t have a political voice, using dress as a means of nonverbal dissemination of your beliefs is really powerful,” says Dr Kate Strasdin, fashion historian and Senior Lecturer in Cultural Studies at Falmouth University.

Historical examples run from the extravagant to the subtle. During the Napoleonic wars, Strasdin explains, women would wear dresses made from calico intricately printed with Lord Nelson’s face to show support for Britain, while in the late 1880’s Oscar Wilde wore a green carnation as a clandestine means of signalling allegiance to other gay men, who were criminalised at the time. And the threads from this history to the present day are clear to see; whether it’s Elliot Page wearing a green carnation to the Met Gala in 2021 or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez referencing the suffragettes and Shirley Chisholm when she wore white to her swearing-in ceremony.

The rise of social media has meant that political and educational touch points within wider culture have become so visual and, because of the platforms they’re consumed on, fleeting, that clothing feels a more potent vehicle for communication than ever. “Generations who might not have lived through certain experiences or who weren’t aware of seminal historical figures are shown [through clothing] where issues have evolved from. Those sartorial connections can be massively impactful,” says Strasdin.

Sartorial connections can be massively impactful

In 2016, a black jumper emblazoned with ‘REPEAL’ in white capitals became a symbol of the campaign to repeal the 8th amendment in Ireland, allowing the government to legislate for abortion. The founder of the Repeal Project, Anna Cosgrave, described it as her “micro contribution to a movement spanning decades”, the jumpers acting as “a stigma buster to open up a conversation on reproductive rights and as a fundraising mechanism for the multitude of volunteer-run organisations working on this issue.”

The key was in the simplicity of the slogan. It got to the heart of the matter and, more to the point, it was inherently shareable. The slogan tee is a wearable placard, that’s been utilised by an array of designers, from originators like Katherine Hamnett to emerging creatives like Kayla Robinson, who want to lay their political cards on the table and help wearers do the same.

But, like anything which has its roots in dissent but grows in popularity, slogan tees have become commercialised. Dior’s SS16 take on Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche’s words cost a cool £490 (it now costs £690) and was largely lumped in with the mid 2010s wave of commodity feminism. Today Shein, which can churn out as many as 10,000 new products a day, sells t-shirts emblazoned with “reduce, reuse, recycle”, and “save the earth”. Sustainable fashion editor Brett Staniland, who shared the styles on Twitter said, “I dunno if I’m laughing or crying real tears.”

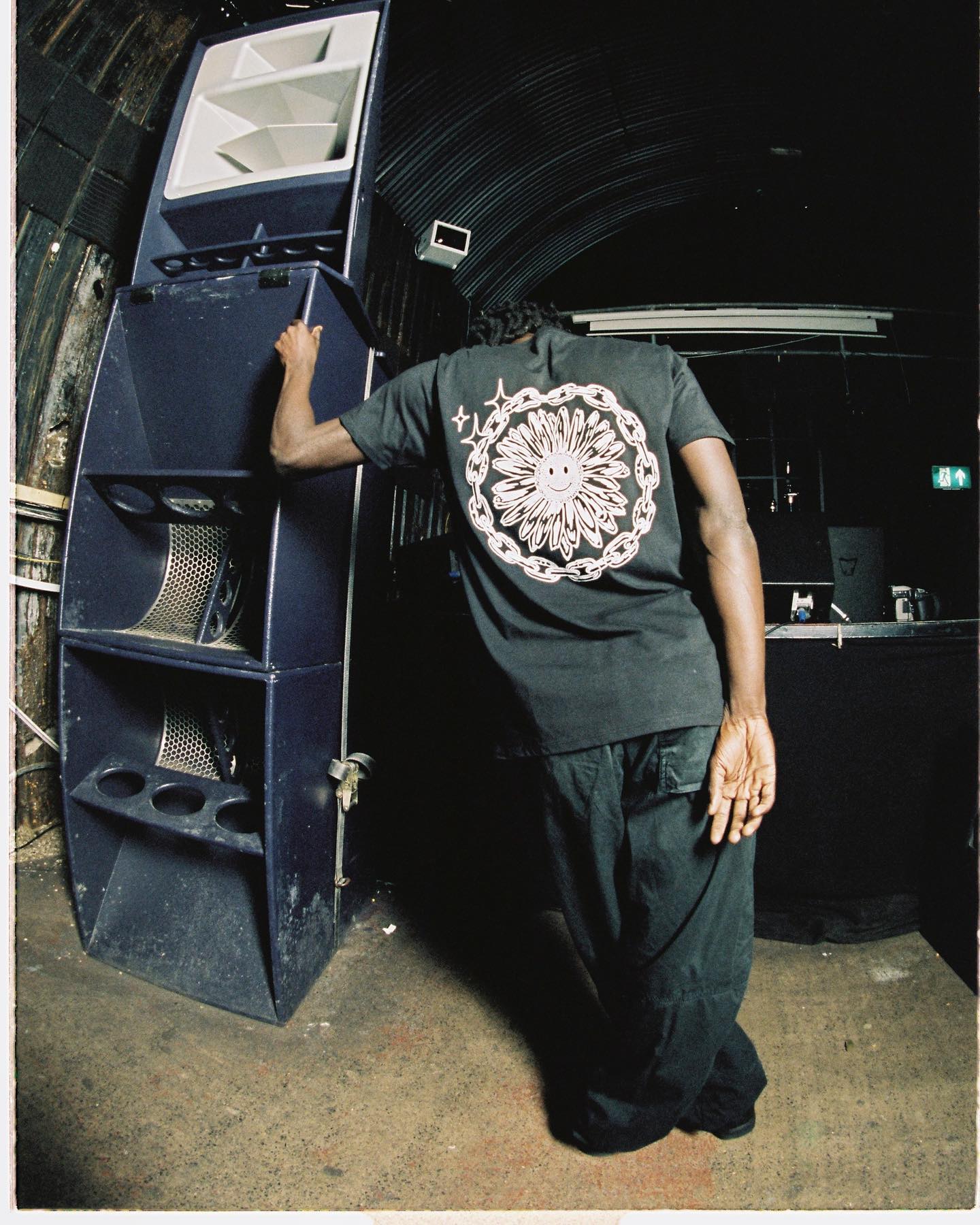

The ease with which the slogan tee has been commercialised and stripped of meaning could be why style, rather than slogans, is back in focus. The alté movement in Nigeria, for instance, which challenges conservative values and supports equal rights for women and the LGBTQ+ community is typified by individualistic, Y2K-inspired style. Crop tops, fishnet, makeup and heels for men, and punk pop meets skate styling are all part of the look. This freedom in style acts as a display of support for the freedom to live the life you want.

President of the Amazon Labour Union Chris Smalls has captured the public imagination not just for his eloquence and determination but for his refusal to emulate the corporate attire of those he’s fighting against. “If I was to run for president, I would look just like this,” Smalls told the New York Times. “I’d walk in the White House with a pair of Jordans on because this is who I am as a person.” (Incidentally, Smalls isn’t afraid of a slogan either, he wore an ‘Eat the Rich’ jacket by Roku Studio to meet Joe Biden at the White House. Predictably, rip-offs have flooded the internet.)

Style, rather than slogans, is back in focus

While Smalls’ casual (and, it has to be said, totally enviable) style is about presenting as his authentic self, others have chosen formality. Stylist Gabriel M. Garmon, when planning a demonstration in remembrance of George Floyd in 2020, encouraged attendees to wear suits, shirts, and ties as a mark of respect. The result was one of the sharpest looking marches you’ve ever seen, reminiscent of the dark suits and Sunday best worn during the Civil Rights marches of the 1960s.

“As a young African-American man, it was powerful to me to see a well-adorned person who had my skin colour. To see how he carried himself, and how he moved. It’s our way of wanting to step forward,” said organiser Eddie Eads.

Criticism often lodged against fashion is that it’s fickle, shallow even. And yes, in some contexts it can be. But for pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong wearing all-black, Black Trans Lives Matter supporters wearing white, or “dripped out trade unionists” on the picket line, fashion and clothing take on a higher meaning. For the collective, they represent solidarity, identity, and defiance.