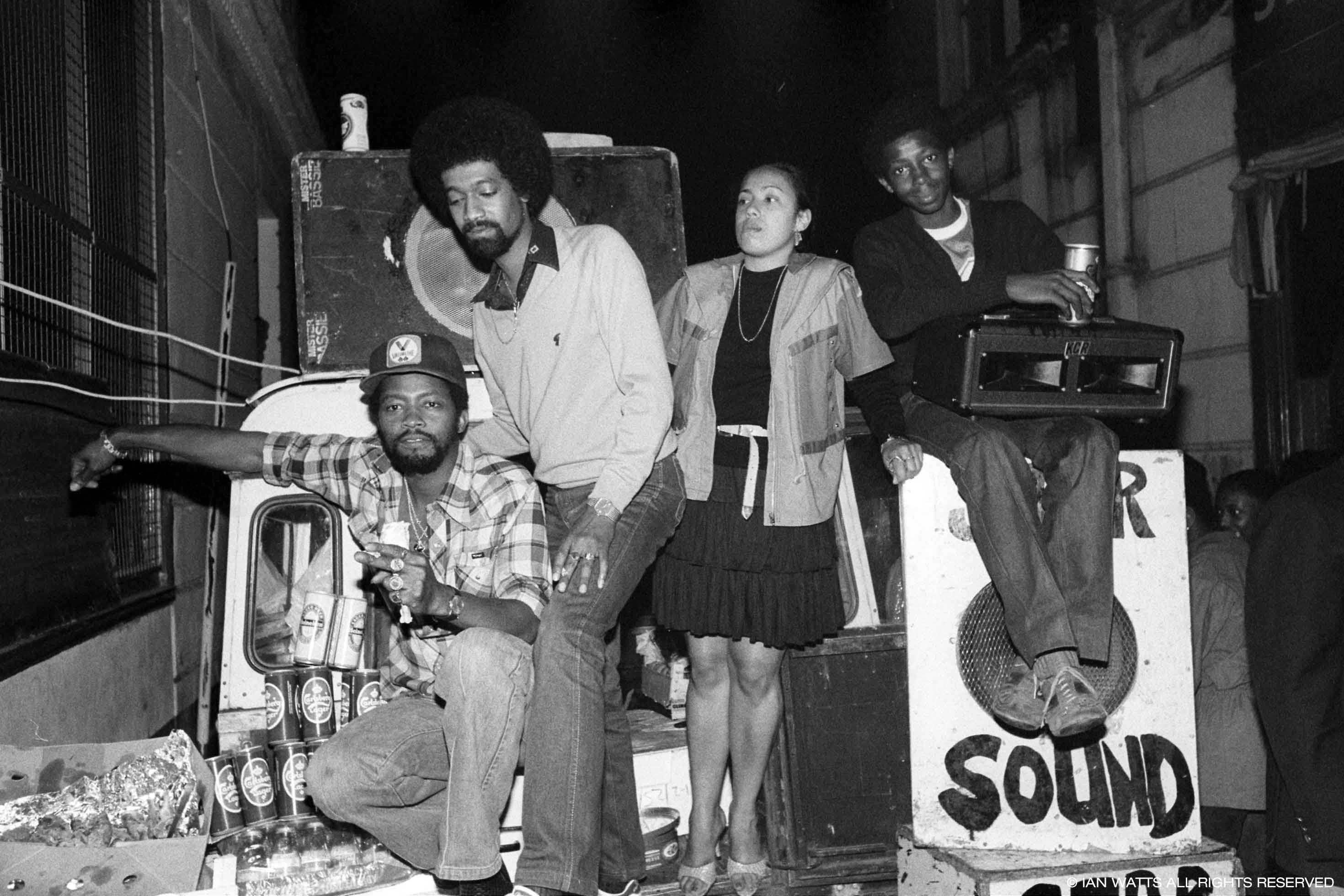

Since the ‘70s Ian Watts has been documenting music, fashion and history across the U.K, Africa and the Carribean. As prolific as he is masterful, his wide-ranging oeuvre spans portraits of iconic figures – Bob Marley, Fela Kuti, Marvin Gaye, Grace Jones, Gil Scot Heron, Miles Davis and James Baldwin among them – insightful series on the UK Reggae and Lovers Rock music scenes, and historical political events in Africa, including the birth of Zimbabwe.

If there is one theme that runs through his work, it’s the unique insight his photographs give into Caribbean and African life in the UK especially. “I have been fortunate to capture and experience many historic black cultural moments,” as he puts it. A Notting Hill Carnival fixture from early on in the festival’s lifespan, Ian’s photographs now comprise a remarkable kind of carnival archive, and were even the subject of an Arts Council sponsored exhibition, Masquerading – The Art of The Notting Hill Carnival.

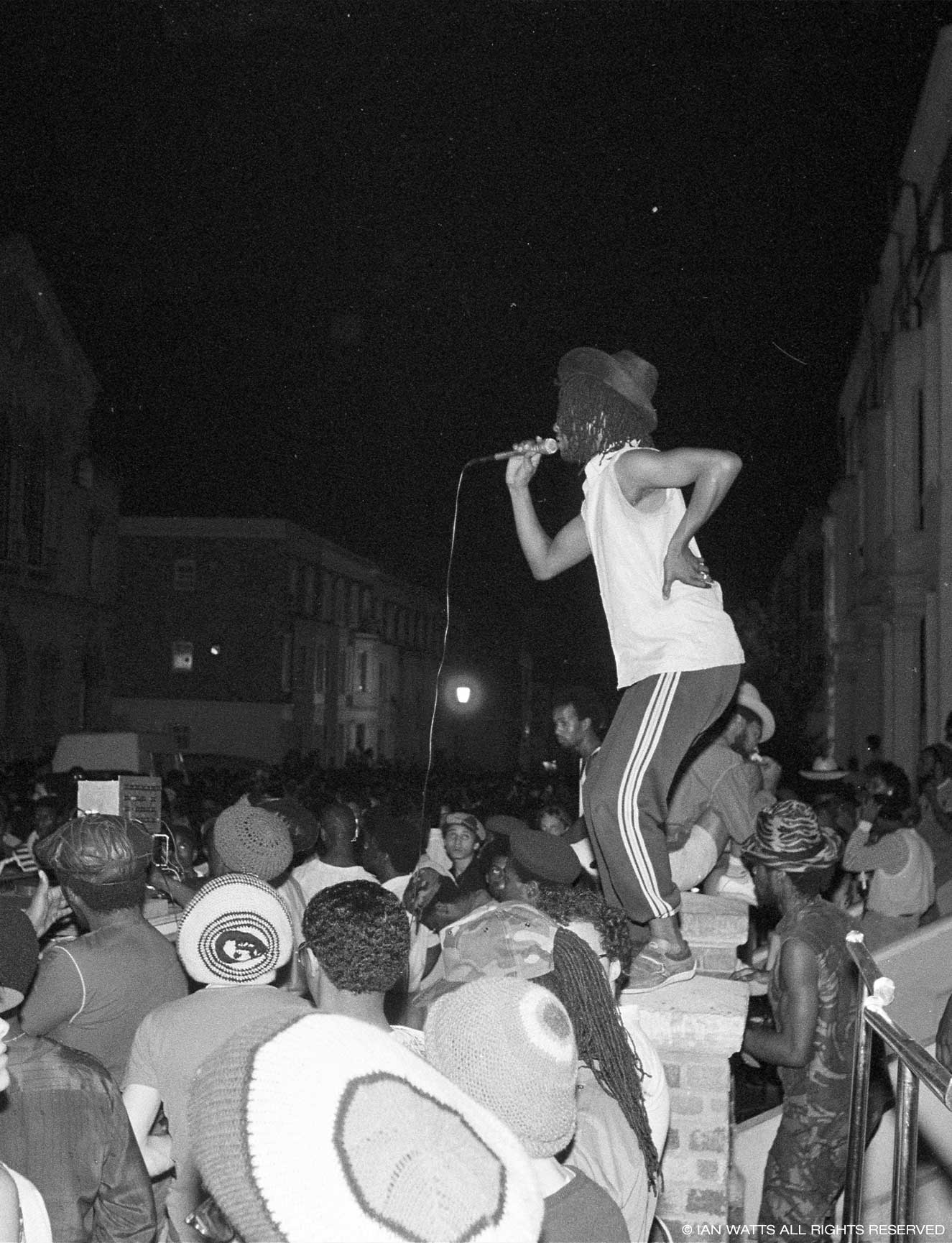

It was unlike anything I had experienced before

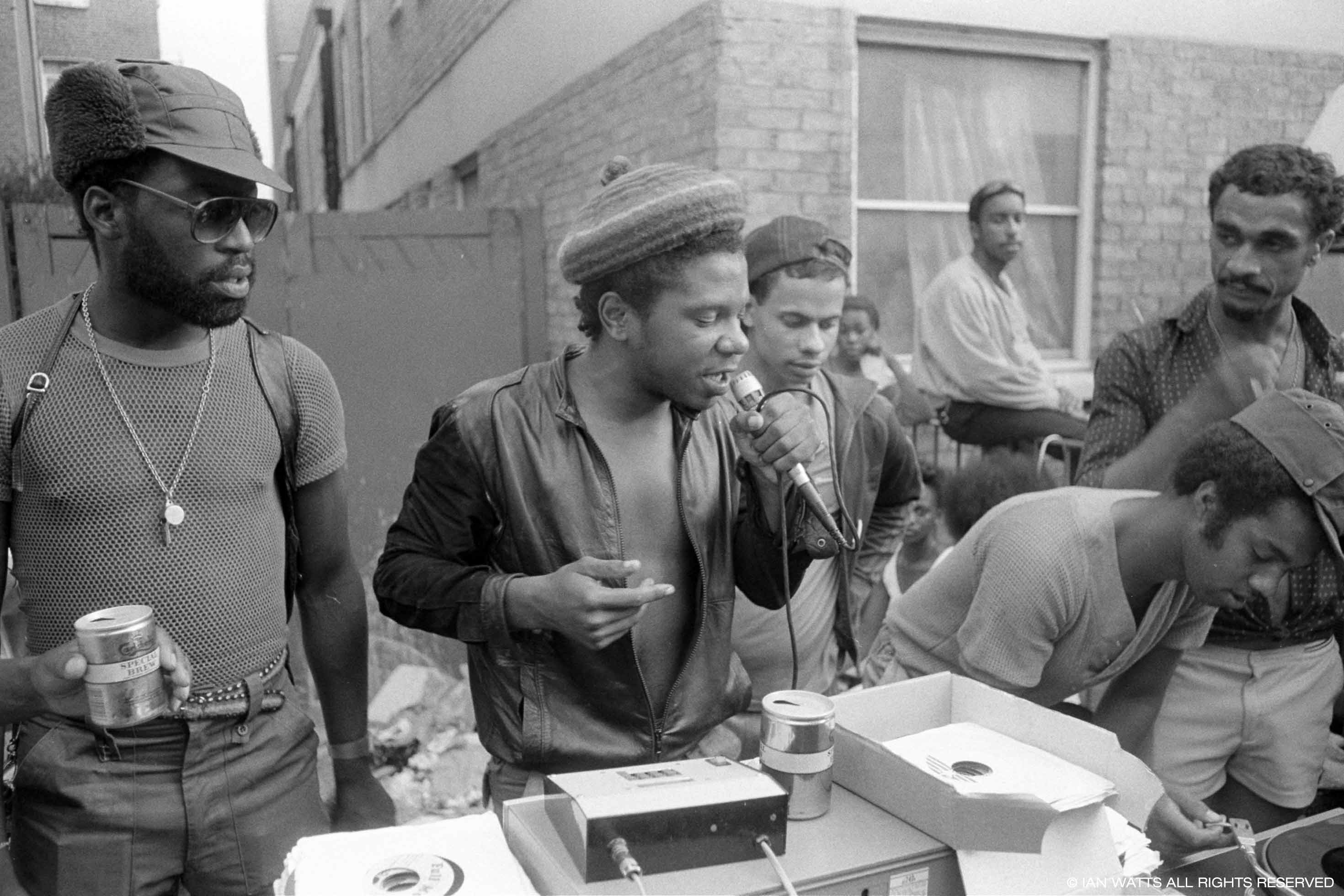

Ian’s relationship with Notting Hill Carnival dates all the way back to 1976, when he was living in nearby Harlesden in North West London. “I went to my first ever carnival in the hot summer of 1976,” he says. “My friends were not really interested in going, so I ended up going on my own. This set the pattern for future carnivals, me going alone so I was free to explore wherever I wanted to go.”

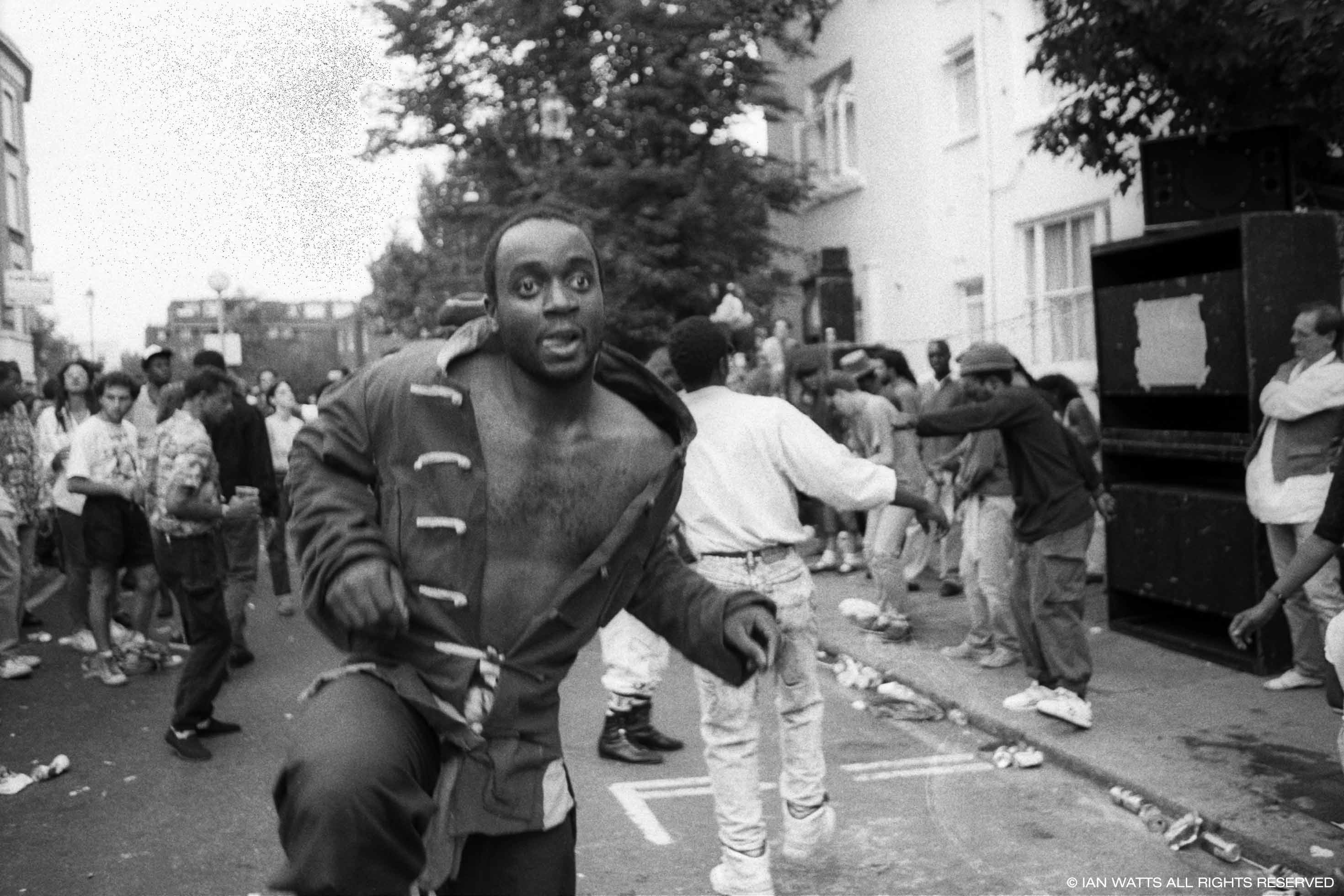

That very first carnival proved to be a formative, seminal experience, both in terms of the photographer’s own life and the career he’d go on to have, and in the wider history of carnival too. “1976 was the year of the first major carnival rebellion and uprisings led by disenfranchised black youth, and I got caught up with the crowd and ended up running with them,” he says. “I actually took some of my first ever photos there with a newly purchased 35mm stills camera, which I was learning to use.”

“It’s something I have never forgotten,” he continues. “This wasn’t just because of the uprising at the end, but also because I had never been to an event like that before, with so many black people. We were listening to floor shattering sound systems; it was unlike anything I had experienced before.”

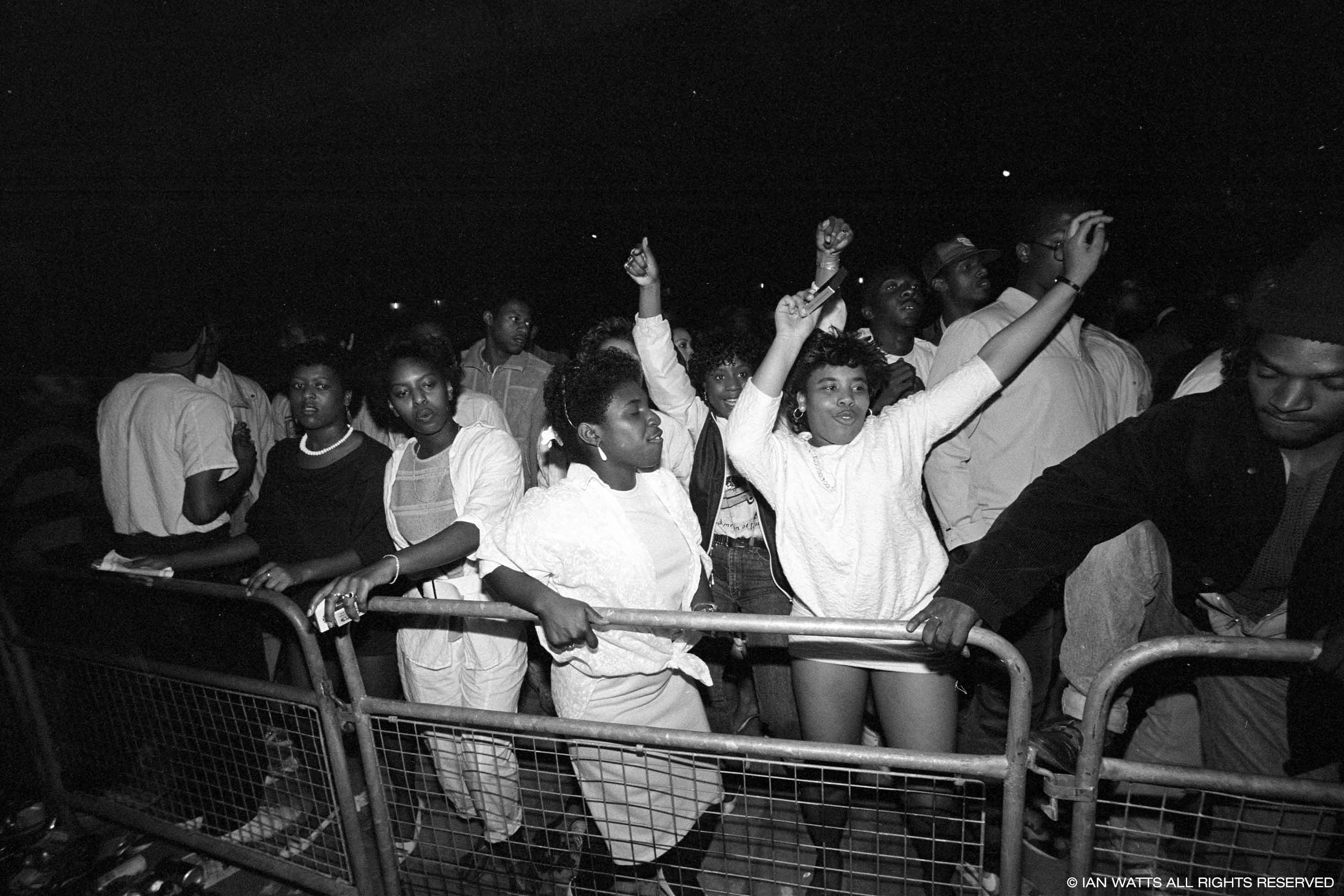

Ian has been back every year since (apart from 2012, when filming in Siberia kept him away) and his joyful, nuanced photographs of the weekend are among the best depictions of the carnival experience in its multifaceted entirety, serving as a counterpoint to the often unfairly negative portrayal that carnival receives. “Carnival is always portrayed as a black experience, and it certainly is, but millions of other people go to carnival and have a great time.” says Ian. “You will never see news reports though, saying that 2.5 million people had a great time at carnival, instead they focus on how many people got arrested. To counter this I cover carnival in a more positive way. I take photos at carnival that resonate with me and capture the black experience in a respectful and empathetic way.”

As Ian makes plain, representing the true spirit of Notting Hill Carnival is necessary and vital, in a wider landscape in which the cultural value and importance of the event is still so often undermined. Even strictly in terms of the direct value it brings to the area, it’s still rare that carnival is given the credit it deserves. “According to the London Development Agency, carnival contributes almost £100m a year to the city’s economy and supports the equivalent of 3,000 full-time jobs,” Ian points out. “Many local shops and businesses thrive through the extra tourist revenue via hotels, restaurants and public transport as a result of carnival. The London Borough of Kensington makes a huge amount of money through licensing stalls and premises, but this is not often recognised.”

Carnival brings great cultural harmony to London

“Carnival brings great cultural harmony to London, which is priceless,” he goes on. “It results in spin-off opportunities that benefit both visitors and participants. It gives people the opportunity to listen to music, eat food, and interact with new and old friends.”

Reflecting too on how carnival has evolved over the years, and whether it’s been able to preserve its original spirit, Ian’s feelings are nuanced. “The original concept [of carnival] lives on, but it has been commercialised by large brands, who don’t always bring benefits to carnival creators,” he says. “I think local people and surrounding areas should get more benefits from hosting this event on their doorstep. Notting Hill Carnival is a great brand, but it has been deliberately marginalised even though it’s been a great ambassador for promoting London.”

Still, for Ian carnival is still an essential space. “At carnival I get the opportunity to listen to music I might never hear again, or at least for a long time. It’s a great opportunity to catch up and bump into old friends and family as well,” says Ian. “I believe it is important to go along and support the event because it is a unique black experience that I’ve always made an effort to attend, even during the difficult times.”

Indeed the ability to capture this complexity might be the essence of Ian’s photographs of Notting Hill Carnival, and what makes them so singular. Of all the images he has taken over the four decades he’s been attending carnival, for him the one that stands out most is one from 1986, of a woman from the Cocoyea mas band in Westbourne Park Road – “It shows the beauty, and also the pain, of carnival.”

Shop Ian’s limited edition ‘UNKNOWN‘ T-shirt, featuring unseen archive photography and typography design by Fieldwork Facility.