SOPHIE BENSON

Sophie Benson is a writer, stylist and lecturer whose work focuses on sustainable fashion, the environment and consumerism.

What is the impact you see this crisis having on fast fashion in the immediate future?

The most important impact to focus on is what’s happening to garment workers in their supply chain. Fast fashion brands are cancelling orders or refusing to pay for what’s already been made and leaving factory owners, and therefore their staff, with no reliable source of income. The margins these brands force factories to operate at are so slight anyway that there’s a real lack of any kind of security blanket. In Bangladesh, the government has offered a fixed sum to help see garment workers through the crisis but it’s enough to cover just one month. Then what? We’re seeing this happening in many major manufacturing hubs.

Hyper fast fashion e-comm brands are clearly still operating with plenty of orders flooding in, as evidenced by their warehouse staff being forced to work in unsafe conditions and their studio staff also being asked to work to shoot the copious amounts of stock that needs shifting. In the short to mid-term at least, these brands still have the resources at their disposal to continue to flourish, so we need to focus on the people they’re leaving behind.

Looking further ahead, what long term effects do you think we might start to see in the industry?

I think we’re obviously going to see a huge downturn in revenue, but for how long, I’m not sure. It’s difficult for brands to plan ahead when the situation is so volatile on a global scale. Companies are letting staff go, shuttering stores and temporarily closing e-comm sites; it’s tough to predict when things will begin to return to normal.

There are so many facets to the industry that each could be impacted in so many different ways in the long term. Will the emphasis on physical fashion week shows decrease? Will brands revisit and shore up their global supply chains as their vulnerability has now been exposed? Will fast fashion brands be forced to slow down? Will small, homemade brands see a boost due to consumer loyalty and a desire to support individuals? Will union engagement rise as employees see how disposable they are to the bosses’ global brands? Will the made-to-order model gain traction as brands mitigate the financial impact of unsold stock? I don’t think there are any firm answers right now but there are plenty of possibilities.

Responsibility should be skewed heavily towards brands

Already there are reports that the effects of cancelled orders on factories will be devastating. Do you think though that any long term positives could come from this, could it serve as a kind of catalyst for change?

My hope would be that the answer to this question is yes. Realistically, I find it difficult to envisage that change coming from brands, unless the action they take will protect their bottom line. I imagine (and hope!) increased scrutiny on the issue will galvanise governments and international organisations to put firm legislation in place to protect the most vulnerable people in supply chains from being abandoned as they have been over the past few weeks.

How much responsibility do consumers have when it comes to fast fashion?

Consumers have as much responsibility as they can afford to have. If you’re living on benefits that barely cover living expenses and you need to clothe yourself and your children then you buy what you can afford, and if it comes from a retailer with dubious ethics then there’s not much you can do about it. Yes, second hand is an option, but it’s not a universal solution. People with disposable income are more able to make ethics-based choices and should do so when they can. It’s a privilege to be able to have this freedom of choice. Collectively we can buy less and change our habits and behaviours but I think responsibility should be skewed heavily towards brands. They hold the power to make the biggest changes and governments should be holding them to account to ensure they do so.

What is the biggest step you can take as a consumer to mitigate the worst of the industry’s practices?

Be vocal, contact your local MP or representative about the issue, engage with NGOs applying pressure to the worst offenders and always, always ask questions.

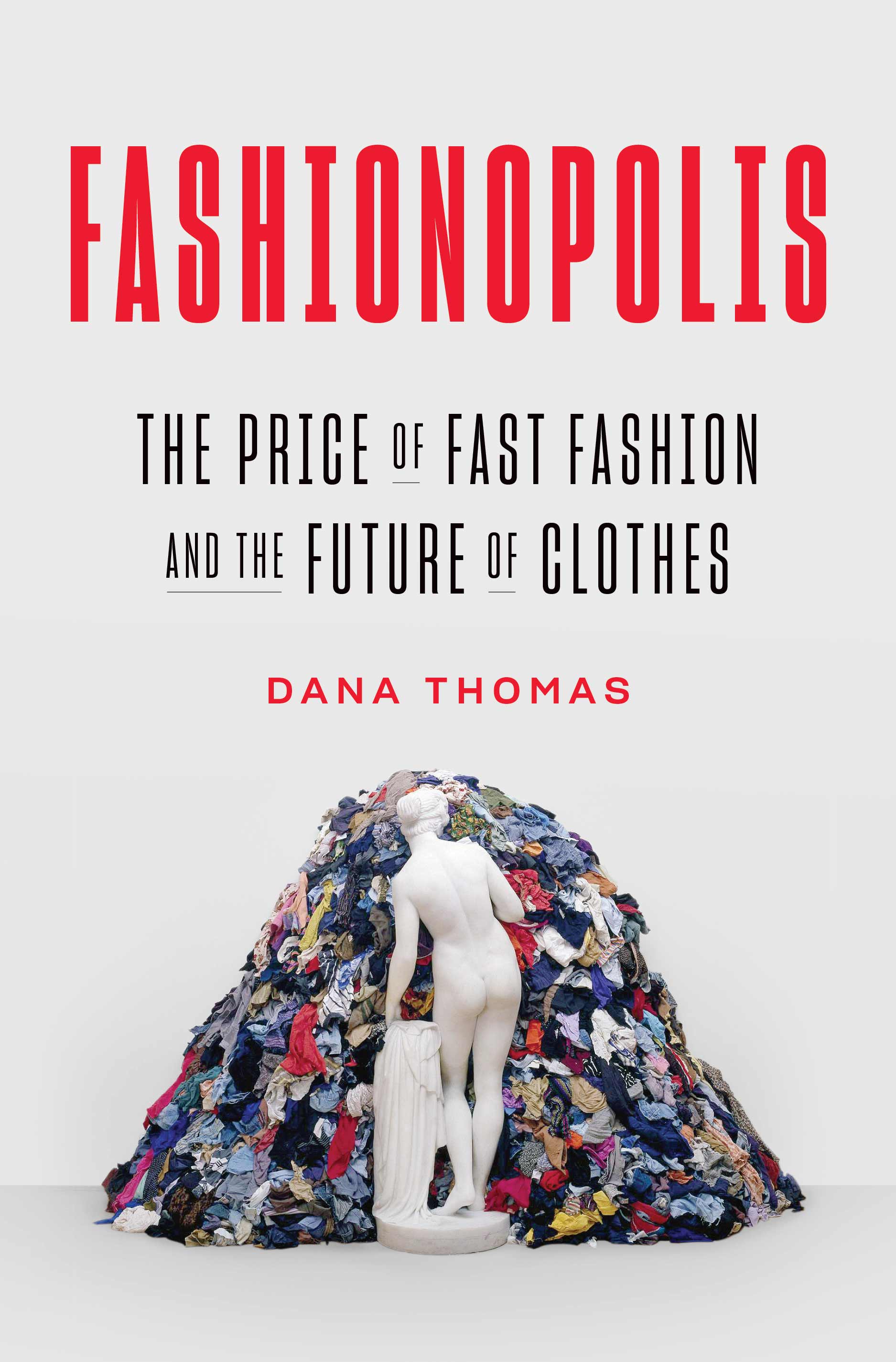

DANA THOMAS

Dana Thomas is a fashion and culture journalist and a New York Times bestselling author. Last year she published Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion and the Future of Clothes, an unflinching investigation into the cost of the fast fashion industry which . She has also written for The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and Architectural Digest, among others.

What is the impact you see this crisis having on fast fashion in the immediate future?

From what I understand, lockdown orders are really walloping fast fashion brands. Most have closed their stores, and are overrun with inventory—since they over order. And some, like Primark, do not have e-tailing, so they can’t move any of that inventory until the stores reopen. Gap laid off 80,000 retail workers when it closed its stores in the US. Already that brand was teetering for a while, and was in the midst of putting in place a turnaround plan. I wonder if they’ll ever be able to turn around now, or if they will follow the lead of Neiman-Marcus, and file Chapter 11. I suspect a lot of stores will never reopen. And I bet there will be some secret inventory destruction.

They’ll think local, and green

Looking further ahead, what long term effects do you think we might start to see in the industry?

I think companies that base their model on volume are going to have a serious think about how and if that will still work. Because, as I’ve said, they are awash in inventory, and it will be really hard to move it.

As for consumers, I think we’ll see more value-conscious dressing. We’ll see less impulse purchases. During confinement, we’ve all had a chance to reflect, and also see that we don’t need so many clothes. There will certainly be more e-commerce, and less bricks-and-mortar shopping. Shopping for fashion right now feels so frivolous, no? I think that feeling will carry on.

Already there are reports that the effects of cancelled orders on factories will be devastating. Do you think though that any long term positives could come from this, could it serve as a kind of catalyst for change?

Gosh, I hope so. I do fear that countries like Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Mauritius will suffer immensely—there will be starvation, because fashion companies aren’t paying their bills and canceling orders. But hopefully this will allow those economies to rethink their structure, and they’ll come up with a new model that is not wholly focused on overproducing cheap clothes to be shipped on the other side of the planet. That they’ll think local, and green. I hope everyone in every business starts thinking more locally and green.

What would you implement to insulate the fashion industry from future shocks like this?

If you are a global company, do not to focus too much on one market—for production or sales. Then if one market is in trouble, you are less exposed.

Remain as nimble as possible—easier when you are a smaller company—then you can pivot more easily.

Aim towards zero debt, so if there is a crisis, you can carry through.

In your opinion, how much responsibility do consumers have when it comes to fast fashion?

Well, this is why I wrote the book. Because we don’t realise as consumers the impact we are having on the planet and humanity with these purchases. We have been conditioned, through marketing, to believe that it’s okay to buy so much for so little money, to burn through clothes. It’s the brands who created the notion of throw-away clothes.

Stop patronising at fast fashion brands. Simple as that.

Once we do know the impact—if via my book, or the media in general—we can make better, smarter choices. Only then is it up to consumers to be more responsible—when they are informed.

What is the biggest step you can take as a consumer to mitigate the worst of the industry’s practices?

Stop patronising at fast fashion brands. Simple as that.

PATSY PERRY

Dr Patsy Perry is a senior lecturer in Fashion Marketing at Manchester University. She co-authored The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion, a recent report which highlighted the extent to which the industry must change to mitigate the environmental impact of fast fashion. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and The Independent.

What overall effects do you think we might start to see in the fast fashion industry, from this crisis?

The cancelled orders will have devastating consequences for workers and businesses, but the fashion system was getting too fast and too big, with constantly increasing volumes of production. There should be less demand for purchasing fast fashion while people are forced to stay at home, and it may be that consumers develop a taste for different ways of dressing, or think more about what to spend their disposable income on.

We have a responsibility to help these countries use the garment industry to lift themselves out of poverty

This might last past the end of the lockdown, especially now that this big change in lifestyle has been enforced for many people around the world. If there’s a downturn economically too, it could force a slowdown which could last beyond the end of lockdown, which is what is needed to help us work towards net zero carbon and also reduce pollution and textile waste.

Already there are reports that the effects of cancelled orders on factories will be devastating. Do you think though that any long term positives could come from this, could it serve as a kind of catalyst for change?

This has shone a spotlight on the precarious working conditions and quality of life for people in the outer reaches of the supply chain, who mostly do not have the safety net of government support or savings to fall back on once orders are cancelled and factories shut down. It has been reported that some of these workers are more concerned about starving than catching the virus, which really puts things into perspective. It shows that we cannot suddenly stop the fashion supply chain, as it would harm people more than if it were to continue, especially in countries which have become heavily reliant on garment exports such as Bangladesh.

But there is a need to vastly improve working conditions so people are not having to take such precarious and poorly paid jobs for the sake of consumers being able to buy cheap fashion. We have a responsibility to help these countries use the garment industry to lift themselves out of poverty, not just keep them in it for the benefit of cheaper prices for consumers.

In your opinion, how much responsibility do consumers have when it comes to fast fashion?

It’s easy to be tempted with fast fashion’s constant stream of new collections and exciting promotional campaigns, but we should also take responsibility for the way we purchase, use and dispose of clothing. We should not think of fast fashion as a disposable item like single use plastic or fast food, even if it seems like it’s marketed to us that way.

What is the biggest step you can take as a consumer to mitigate the worst of the industry’s practices?

Be more selective in your purchases, only buy things you really love and will wear again, or consider renting, swapping or shopping second-hand, and that way you will extend the useful life of clothing already in existence, which helps to reduce the environmental burden of producing more new things.

FLORA DAVIDSON

Flora is co-founder of SupplyCompass, a platform that helps enable fashion brands and manufacturers to work together sustainably. A large part of SupplyCompass’ work is in digitalising global supply chains, in order to make sustainable sourcing easy and cost effective for brands.

What is the impact you see this crisis having on fast fashion in the immediate future?

The current situation is impacting businesses around the world in different ways, though its impact is undeniably felt the most amongst the lowest paid workers across supply chains in developing nations. In the majority of countries where fashion production happens, workers don’t have the luxury of government-supported furlough schemes. Most factory workers are unable to work, meaning they are going unpaid until international lockdown ends. Even when workers are allowed to start returning to their factories, situations will be uncertain and will depend heavily upon what happens with consumer confidence and demand across the globe.

there is a short window of opportunity for experimentation

Fast fashion has been forced to slow down, or in some cases, come to a screeching halt. It’s likely many brands will proceed cautiously, skip seasons and plan scaled back collections. International supply chains will take time to get back up and running to the same efficiency post lockdown, with many manufacturers never able to reopen. COVID-19 has affected cotton sewing, growing and picking cycles – with the past four weeks a crucial time for many cotton farmers around the world. The financial implications of this may not be known by farms until next year.

Looking ahead, what long term effect do you think we might start to see in the industry

While ‘normal’ ways of working have been turned on their head, there is a short window of opportunity for experimentation. I am hopeful that this crisis will be a catalyst for change, and that the next few months will usher in a new and better era for the fashion industry. I’m already seeing businesses take the time to explore new solutions and be more open than ever before. If we look at how fast everyone has adapted to this new normal in response to the global pandemic, imagine what other changes businesses could make? This could place sustainability and technology at the heart of this transformation. Rather than reverting to how things have always been done, I see an opportunity here for brands to reinvent, adapt and experiment with new technologies and methods of working. Adapt to survive – perhaps some businesses may even prosper unexpectedly as a result!

If this could be a positive catalyst, what would a more sustainable industry look like?

The sustainability conversation focuses heavily on the environment, often overlooking the importance of sustaining the livelihoods of the people working across the value chain. For us, when we talk about sustainability, it encompasses balancing people, profits and planet. For brands wanting to be ‘sustainable’, this starts with good buying practices. This means honouring commitments, riding this storm with their supply chains and planning for the future. It takes years to build good relationships and reputations, but both can be lost overnight in times like these. Hopefully the fashion industry will start to truly consider supply chains as central to its existence and integral to its success.

What would you implement to insulate the fashion industry from future shocks like this?

It’s really important to know your supply chains. Supply chain transparency and traceability is important regardless of an impending crisis. Full traceability means going beyond tier 1 manufacturers, making sure to know your mills, spinning units and dye houses, too. If you don’t know where your organic cotton is being grown, ginned and spun, for example, you won’t know where your supply chain will be impacted. With full visibility, business will be able to anticipate, manage and mitigate risk in the future.

Focus on relationship building. This is always important, but now more than ever. We’ve all read the news where brands have broken long-term trusted relationships with their factories, refusing to commit to orders placed. In times like this, the strongest, most resilient relationships can be cemented. Supply chains are fundamental to the success of a fashion brand; factories should be considered as strategic partners. Focus on building personal relationships, rather than having transactional interactions with factories. It is worth investing time into this now.

In your opinion, how much responsibility do consumers have when it comes to fast fashion?

As consumers we play a huge part in the rise and success of fast fashion. The change needs to come as much from us as from brands and policy makers. Ultimately, brands today really listen to what their consumers say and want; it’s a competitive climate out there! If their customers express enough interest in doing things better, they will see it is important too and make changes as a result.

What is the biggest step you can take as a consumer to mitigate the worst of the industry’s practices?

Do your research, keep asking questions and try not to buy on a whim. Take the time to read up about a brand before you buy from them; remember, often the information you can’t find is as important as the information you can. It takes time to read around and everyone has busy lives, so I love the app Good On You. They do a lot of the hard work for you and present information on thousands of brands in a really digestible way. I’m also a massive Depop lover, so secondhand is always a good option. I think it’s about paying extra for quality clothing because at the end of the day, cheap clothes don’t resell well either!

Read More: Sustainability 2.0 | The Evepress Sustainability Roadmap